Welcome to Scratch 3!

Jan 16, 2019

What’s changed with Scratch 3 - lower floor, wider walls, same high ceiling.

Over the years it’s been with us, Scratch has had a profound impact on computing education. Many children’s first experience of coding is through Scratch, with the block based, visual interface making it easy for anyone to get started. The building block inspired approach encourages playful experimentation and fosters learning through discovery. The global community of Scratchers provides inspiration, an audience and encouragement at all stages. Scratch has provided a starting point and inspiration for many other block-based languages, and analysis of the corpus of Scratch projects (or just a subset of it) provides some great insights into children’s understanding of computer science.

A new version of Scratch then is something of a milestone for all of us coding or teaching with it, and for the computer science education community more generally. As Mitch Resnick highlights in his introduction to this month’s cover feature, much has not changed in the upgrade from version 2 to 3, and the Scratch team deserve credit for remaining true to their core principles, prioritising simplicity and accessibility. Computing education pioneer Seymour Papert emphasised the need for a low floor and a high ceiling in technology for learners: it should be easy to get started, but there should be no limit to how far you might take things. Resnick adds to this the idea of wide walls, of many paths up from the floor toward the ceiling. Scratch’s new version addresses all three of these elements very effectively.

Low Floor

Scratch 3 makes it easier than ever to get started. There’s now a built in set of tutorials, which you might think of as akin to the build instructions that come with sets of LEGO - you certainly don’t have to use these step-by-step guides, but following the plans here gets you started and many may find this less intimidating than staring at a blank editor window.

The editor has been simplified somewhat. The coding window and the stage have swapped over, bringing the layout back to what we had in version 1. We’ve lost a few of the lesser used tools, and the grouped palettes of blocks are now in a single, scrollable list, making it much easier to find the block you’re looking for. Some of the less frequently used commands (those for turtle graphics, music and the webcam) have become extensions (see below…).

When getting started with teaching (or learning) Scratch, it’s easiest to use the built-in library of sprite costumes and backgrounds. It’s lovely to see how these have been expanded, with some really high quality artwork added to provide inspiration to young coders.

Costume and background image editing has been improved, as has the sound editor (check out the cool Echo and Robot effects).

The move from Flash to HTML / Javascript is very welcome, not least because this makes it much more accessible. Scratch, at last, now works on tablets such as the iPad via the browser. Things like text search and screen reading work in Scratch 3 if they work in the browser. The language pack can be changed just as easily, and rather wonderfully selecting Arabic and Hebrew swaps the interface and blocks over to suit right to left reading.

Wide Walls

Scratch has always supported a wide range of contexts for young people to learn coding: it seems such a shame that in schools many teachers focus on just animations and games, great as they may be. In Scratch 2, a number of extensions were available through ScratchX, but Scratch 3 brings the best of these into core Scratch, as the equivalent of standard libraries. Interestingly, some of the functionality that was built-in to Scratch 1 and 2 now moves into extension, I think with the aim of making the new version that bit more accessible, whilst still keeping this functionality present for those who want it. The pen tool for turtle graphics is now one of the extensions, as are the MIDI-like music blocks: I find both of these great for introductory lessons, and so hope that there move into extension land won’t mean these great tools get overlooked.

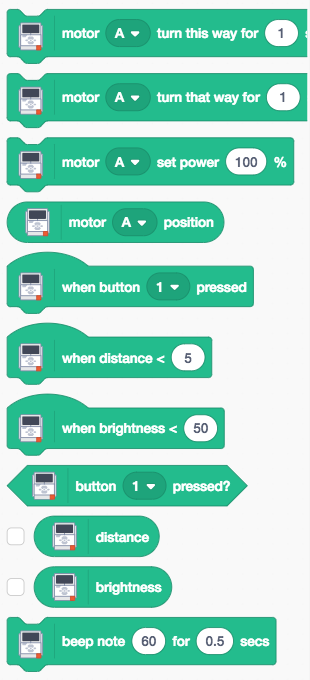

Physical computing is now well supported - ranging from simple input controls with MaKey MaKey and the micro:bit, through to robotics using LEGO’s WeDo 2 and Mindstorms EV3 kit. Connectivity via Bluetooth to the LEGO kit is really rather nice - using one family of building blocks to control another family of building blocks.

The extensions also make it possible to use some machine learning tools here: at launch we’ve text to speech, which I hope will get Scratchers thinking about how to make there programs a bit more accessible to those who struggle with text on screen, and Google powered machine translation - we’ve a quick demo of both presented as a lesson plan further on in this issue. The extension architecture is open to other developers to use with the support of the Scratch team - I’ve seen demos of speech to text, and I suspect image recognition won’t be too far away: see David Horton’s experiment with an AI powered version of rock, paper, scissors in Scratch for one idea of what we could do with this.

High Ceilings

It’s not immediately obvious how Scratch 3 extends the ceilings of what young programmers can do. Where Scratch 2 gave us the ability to create our own blocks and pass parameters to them, there’s no similar pushing the limits of the CS we can teach with Scratch in this version (I’d have loved to see functions this time round…), but then again, perhaps there doesn’t need to be? Scratch is already a Turing complete language, and so any problem that can be solved using a computer can (at least in theory) be solved in Scratch: how high do the ceilings need to be?

There are plenty of languages that folk can move on to from Scratch: I think Snap! is ideal as a second, block-based language, and the path from Scratch to Python is oft-trodden and well documented. On the other hand, it’s worth exploring the Scratch community to see just how far young people have taken Scratch themselves, typically outside of the classroom, using Scratch fluently as a medium for creative expression rather than just as a means of learning to code - Scratchers’ involvement goes way beyond coding though: it’s at its most impressive through participation in the community - liking, commenting, remixing, curating, supporting. Important as computational thinking and coding may be, I suspect it’s actually these softer, participatory skills that will serve these amazing young people best in the long term.

Originally published in Hello World 7

Share