Revisiting computational thinking

Apr 03, 2019

‘Computational thinking’ is seen as the golden thread running through England’s computing curriculum and its development provides a key argument for the (re)introduction of programming into education systems across the world. In England, the computing programmes of study open with the ambitious view that

‘A high-quality computing education equips pupils to use computational thinking and creativity to understand and change the world.’ (DfE 2013)

Other jurisdictions emphasise the importance of problem solving in computing education, recognising that, whilst not every student will end up as a software engineer or computer scientist, teaching everyone to program will help them to develop as computational thinkers, and that this is something that will be useful for everyone. As Jeanette Wing argued back in 2006:

Computational thinking is a fundamental skill for everyone, not just for computer scientists. To reading, writing, and arithmetic, we should add computational thinking to every child’s analytical ability. (Wing 2006)

More recently, the OECD’s Andreas Schleicher has cast doubt on the global movement to teach ‘coding’, but nevertheless argued that he would be much more inclined to teach data science or computational thinking than to teach a very specific technique of today (Turner 2019).

This emphasis on ‘computational thinking’ is even reflected in current arrangements for assessing computing at GCSE, where actual coding, although a formal requirement of the specification, carries no marks, although 50% of the grade is given for ‘computational thinking, algorithms and programming’ (OCR 2018).

Given, then, the centrality of computational thinking to computing curricula and assessment, it would be reasonable to expect some clarity about what this is, and perhaps even some consensus around how it might best be taught in schools. Unfortunately, I fear there remains confusion over what computational thinking is, and thus ongoing issues over how it should be taught. I’d like to use this short article to address these issues.

Back in 2006, Wing gave a definition of computational thinking:

Computational thinking involves solving problems, designing systems, and understanding human behavior, by drawing on the concepts fundamental to computer science. Computational thinking includes a range of mental tools that reflect the breadth of the field of computer science (Wing 2006).

Unfortunately, this idea of taking the ideas of computer science and applying them to other domains is rather too vague to be of much practical use: we end up with little more than ‘problem solving skills’ with some connections to the concepts of computer science. Regratably, this sort of vague interpretation of computational thinking was the one picked up by the Royal Society in the Shutdown or Restart report:

Computational thinking is the process of recognising aspects of computation in the world that surrounds us, and applying tools and techniques from Computer Science to understand and reason about both natural and artificial systems and processes. (The Royal Society 2012, p29)

An understanding of the principles of computer science gives us a better understanding of, well, computer science. It doesn’t, on its own, make us any better at music, history, or physics, or generic problem solving. To get better at music, history or physics, study music, history or physics respectively. As Tedre and Denning argue,

Computational thinking […] offers very powerful mental tools for people who design computations. There is no need to make exaggerated claims—notably automatic transfer of CT skill across domains or about superiority of CT over other ways of thinking and practicing.

Mark Guzdial goes further:

The challenge to computational thinking is the problem of knowledge transfer. Applying computing ideas to facilitate computing work in other disciplines is clearly achievable. Applying computing ideas in daily life is less likely. There has not been a study since Wing’s 2006 paper that has successfully demonstrated that students in a CS class transferred knowledge from that class into their daily lives. (Guzdial 2016)

That’s not to say that computer science doesn’t offer particular insights into other domain: of course it does, as witnessed by advances such as generative art, the digital humanities and computational science, but these advances haven’t come about merely through the application of the principles of computer science to these domains, they’ve come about by actually using computer programming to solve problems in these domains.

It’s this, I think, that’s key to a proper, and useful, understanding of computational thinking. In short, computational thinking without computation is just thinking.

More recently, Wing has adopted a rather more helpful definition of computational thinking, which sites computational thinking within the broader territory of problem solving, and recognises that computational thinking is distinguished from other approaches through its solutions being ones which computers can carry out:

Computational thinking is the thought processes involved in formulating a problem and expressing its solution(s) in such a way that a computer—human or machine—can effectively carry out. (Wing 2017)

The key then in computational thinking is looking for solutions to problems that are automatable: that could be carried out by a machine, or perhaps by people acting as machines. To take one common example, it’s not computational thinking to come up with a recipe for jam sandwiches, but it is computational thinking to come up with a way of making jam sandwiches which can be implemented by a production line, whether that’s staffed by robots or people.

Finding solutions to problems that can be automated is rather a rather more modest vision for what we should be teaching, but it’s still really quite important - there’s hardly any domain of study or employment where computers aren’t already helping us to get previously hard things done more easily and providing new insights and creative opportunities. Computational thinking of this sort really does help here. Furthermore, it gives teachers something they can practically teach and assess: teaching computational thinking becomes less about making sandwiches and more about thinking how to write a program to solve a problem; assessing it becomes less about parroting definitions, non-verbal reasoning puzzles or spotting patterns and more about writing programs that solve problems.

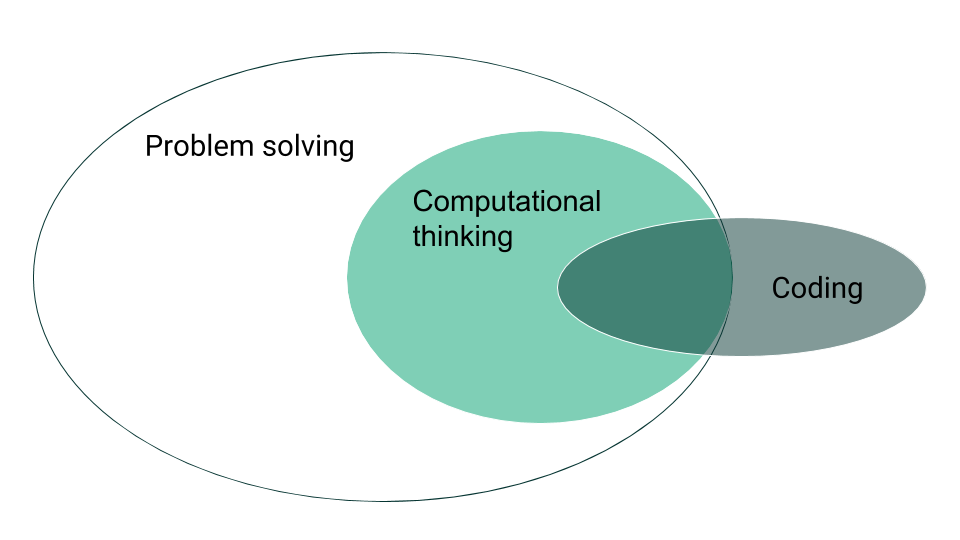

I think the relationship between problem solving, computational thinking and coding looks a little like this:

Not every time we try to solve a problem are we looking for a solution that can be automated (indeed, automating solutions to problems seems to be frowned on in much school mathematics these days), but sometimes we are, and it’s on those occasions that the processes of computational thinking come into their own. When we actually do implement those solutions on a computer, typically we’re writing code, i.e. instructions that both the machine and the programmer can both understand. I deliberately use the word ‘coding’ here, rather than ‘programming’, as the latter should be seen as including the computational thinking necessary to work out how to solve the problem: i.e. programming is algorithm plus code. Not all coding is inside the computational thinking hoop here: too much of the time in school I fear we try to teach coding without the computational thinking that should come before it: children simply follow the steps they’re given, or just tinkering aimlessly with blocks. In those circumstances it’s no surprise that just learning to ‘code’ has little if any impact on what might be assessed as computational thinking (Pea 1983, Straw 2017).

Barefoot Computing and others have attempted to break down computational thinking into a number of concepts, approaches or processes. Typically, these lists include decomposition, algorithms, patterns and abstraction. All of these are of direct importance in computer programming, and thus the computational thinking necessary to find an automatable way of solving a given problem. They also occur in other contexts too, away from computer programming. Perhaps in keeping with Wing’s earlier notion of applying the fundamental concepts of CS to other domains, or perhaps because teachers want their pupils to understand these aspects of computational thinking, these often get taught in isolation. Thus, for example, pupils might learn about decomposition as the different parts of a plant, algorithms as the sequence of steps they follow to make toast, patterns in nursery rhymes and abstraction as the storyboard for a film. These are all well and good as ways of giving pupils some grasp of these individual ideas, but they’re really quite unsatisfactory as examples of computational thinking, as none of them result in the solutions to problems which could be carried out by computers, and it’s finding these sorts of solutions is what computational thinking means!

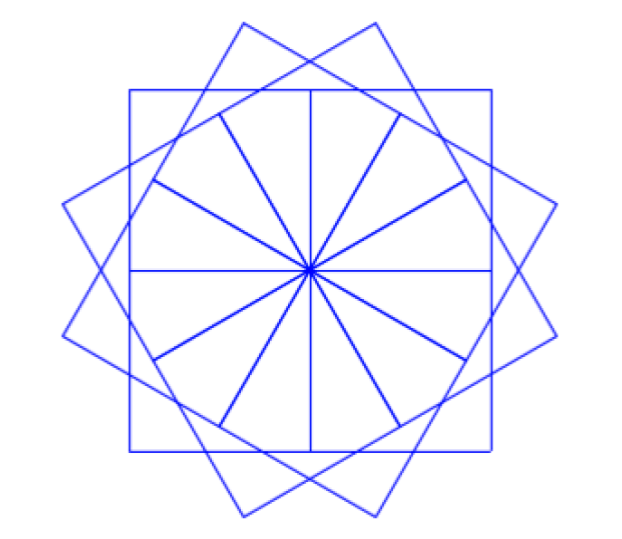

The point of teaching concepts such as decomposition, algorithms, patterns and abstraction is not that these can be applied to solve problems in other domains or in everyday life, but that they help us to write programs, and its those programs that can (and should) be applied to solving problems in other domains or in everyday life. Consider a simple turtle graphics problem such as drawing this:

To write a program for the turtle (or someone acting as the turtle), you need to break down this complex shape into component parts (12 squares, or perhaps three window frame like structures), recognise that each component can be drawn using the same pattern of instructions, identify the algorithm for drawing each, and work at an appropriate level of abstraction (programming the turtle, rather than worrying about colour values for each pixel on the display).

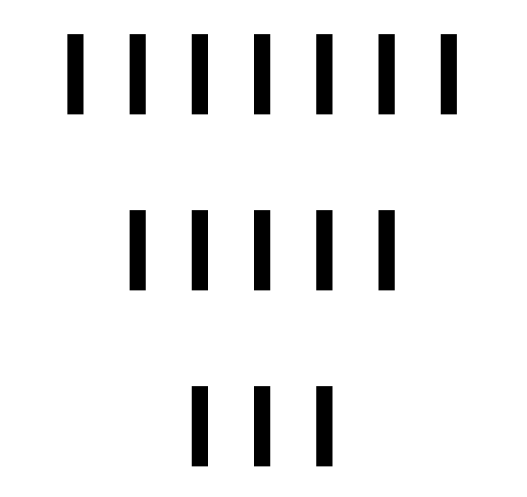

Or writing a program to play the game of Nim (players take turns to remove 1 or more matches from a chosen line, aiming to take the last match themselves).

Again, the concepts of computational thinking can be applied directly here: we might decompose our approach to create a model of the game and its rules, a way to display the board at any point in the game, and a way of the human player selecting their moves. We’d might explore the patterns in winning moves, using these to establish the algorithm the computer should follow to play these moves. We’d use abstraction to recognise that the position of pieces within a row is irrelevant, as is the order of the rows. It’s hard to see how you could program the computer to play Nim without drawing on these ideas.

This approach to teaching the elements of computational thinking: holistically, to solve a problem, and with a program as the outcome, seems much more practical than attempting to teach each in isolation, and, I suspect, is also likely to result in pupils who become that little bit more competent at programming. Will teaching computational thinking this way make pupils any better at music, history or physics? Well, probably not, but I don’t really think the other way would either. At least this way, they might stand a good chance of taking some problems from music, history and physics, and then writing decent code to find solutions to them.

References

DfE. 2013. The national curriculum in England. July. London: DfE.

Guzdial, Mark. 2016. Learner-centered design of computing education: research on computing for everyone. Williston, VT: Morgan and Claypool.

OCR. 2018. GCSE (9-1) Computer Science J276. Coventry: OCR.

Pea, RD. 1983. Logo programming and problem solving. In American Educational Research Association, Chameleon in the Classroom: Developing Roles for Computers. Montreal, Canada.

Straw, Suzanne, Susie Bamford, and Ben Styles. 2017. Randomised Controlled Trial of Code Clubs. Slough: NFER.

The Royal Society. 2012. “Shut down or restart?” January. London: The Royal Society.

Turner, Camilla. 2019. Teaching children coding is a waste of time, OECD chief says.

Wing, Jeannette M. 2006. “Computational Thinking.” Communications of the ACM 49 (3):33–35.

Wing, Jeannette M. 2017. Computational thinking’s influence on research and education for all. Italian Journal of Educational Technology 25 (2):7–14.

Originally published in Naace’s Advancing Education journal

Share