Time for change?

Sep 18, 2019

Somewhere close to the start of the English maths curriculum, pupils learn to work with coins, initially as physical manipulatives, then as icons and eventually as numbers. By the age of seven or eight, pupils are taught to “find different combinations of coins that equal the same amounts of money”. This sounds quite straightforward.

Finding the smallest number of coins to make a particular amount of money is something we do without consciously thinking about it, but if you had to teach a child to do this, what method would you suggest? It’s something which machines can do too: vending machines give change; good vending machines give change using the smallest number of coins they can. How would you program a vending machine to do that?

A greedy algorithm

It’s a problem that lends itself to a greedy algorithm:

- start with the largest value coin

- keep giving that coin until the amount left is less than the value of * the coin

- move on to the next largest value coin and do that again,

- keep moving on to the next largest value of coin until there are no more coin values left.

Following this algorithm by hand seems to give the answers we expect. E.g. 38p change: 20p, 10p, 5p, 2p, 1p.

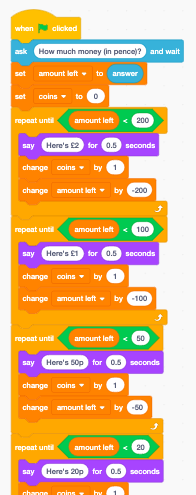

A näive approach to coding this in Scratch might look a little like this:

(see scratch.mit.edu/projects/123785554/)

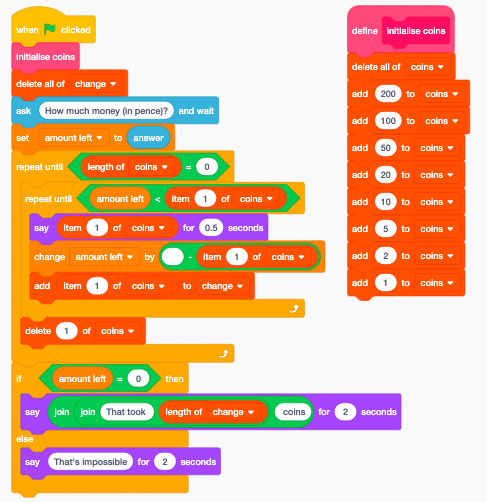

As pupils become more fluent with programming in general and Scratch in particular, they might make use of more procedures for dealing with each coin value in turn or perhaps lists for the coin values and the coins needed.

(from scratch.mit.edu/projects/294675404/)

Whilst the maths here is on Year 2 of the primary curriculum, I don’t think we’d expect Year 2 to be able to write Scratch code to work out the solution, but by the end of primary, I’d hope that most pupils would be able to create a version of this in Scratch themselves. At some point in Key Stage 3, I’d hope that pupils could make the transfer over to coding the same algorithm in Python, perhaps along these lines:

def fewestCoins(amount, values=[200, 100, 50, 20, 10, 5, 2, 1]):

coins = []

for value in values:

while amount >= value:

coins = coins + [value]

amount = amount - value

return coins

This works well enough for English coins. We can generalise this though: it’s easy enough to modify it to work with US coinage too, with English pre-decimal (or post-Brexit?) currency, and with the equally Byzantine Galleons, Sickles and Knuts if you find yourself teaching programming at Hogwarts.

Bit coins?

But look, it works well enough for this set of coins too: 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1. That is, the binary place values for eight bits. For example:

38p = 32p + 4p + 2p. 99p = 64p + 32p+ 2p + 1p.

And so on.

Given the ease with which pupils can find the smallest number of coins for amounts, I think a set of, let’s call them, bit-coins, perhaps first as manipulatives, then as pictures, finally as numbers, could be the easiest way to get pupils converting numbers to binary.

The above Python code works well enough for working out the bit values, and could be used for other number bases too – use 64, 8 and 1 to get octal. Use 16 and 1 to get hexadecimal. I think a coin-based model such as this goes a long way to internalise an understanding of the maths here.

If we’d like to actually get the binary out, then a little remixing is needed.

def decimalToBinary(decimal):

bitValues = [128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1]

bits = ""

for value in bitValues:

if decimal >= value:

bits = bits + "1"

decimal = decimal - value

else:

bits = bits + "0"

return bits

However…

All this looks great, doesn’t it? We’ve got a general algorithm here to solve all sorts of coin decomposition problems, and have generalised it to convert numbers from to binary and even to other number bases.

The problem is, this algorithm doesn’t always work.

What about coins worth 1p, 10p, 20p and 25p coins. How would you make 40p? If you follow the greedy algorithm, you’d use a 25p, 10p and five 1p coins, so that’s seven coins in all. If you stop and think a bit, you might decide that just two, 20p coins would be better! How come the greedy algorithm brakes down here?

Or, imagine that we only have 7p and 9p coins. What combination would you use to make 47p? My Python code happily returns five 9p coins, but that’s wrong! You can’t make 47p using just 7p and 9p ‘coins’. Why not? You can, however, make any amount bigger than 47p, although my greedy algorithm gets most of these wrong too.

Coming up with an algorithm that works for these situations too is a bit more tricky, but one approach relies on the recursive nature of the problem. Sticking with the English coinage, to make 38p, you could start with a 20p and make 18p, or start with 10p and make 28p, or start with 5p and make 33p, or start with 2p and make 36p, or start with 1p and make 37p. So the smallest number of ways to make 38p has to be one more than the smallest number of ways to make 18p, 28p, 33p, 36p or 37p, whichever is least.

Our recursive rule here looks like:

minimumcoins(x) = 1 + minimum (

minimumcoins(x-200),

minimumcoins(x-100),

minumumcoins(x-50),

minimumcoins(x-20),

minimumcoins(x-10),

minimumcoins(x-5),

minimumcoins(x-2),

minimumcoins(x-1))

With the base cases that minimumcoins for 200, 100, 50, 20, 10, 5, 2 and 1 are all 1, as the smallest number of coins needed to make 50p is pretty trivial!

Generalising this for any set of coin values gives us this recursive Python code:

def fewestCoinsRec(amount, values=[200, 100, 50, 20, 10, 5, 2, 1]):

minCoins = amount

if minCoins in values:

return 1

else:

for thisCoin in [value for value in values if value <= amount]:

numCoins = 1 + fewestCoinsRec(amount - thisCoin, values)

if numCoins < minCoins:

minCoins = numCoins

return minCoins

This, though, is incredibly slow – my 38p with English coins example takes over 37 million calls to the recursive function, and takes nearly 30 seconds to run on my poor Mac Book. I suspect most Year 2 children would be quicker!

There are things we can do to speed this up – using a dictionary to keep track of the minimum coins found so far for each amount we look up helps. If we go to the trouble of keeping track like this, it’s actually faster to build up the dictionary from the bottom up – with English coins, you need 1 coin to make 1p, 1 coin to make 2p, 2 coins to make 3p, 2 coins to make 4p, 1 coin to make 5p, and so on. To find out how many coins you need to make 6p, you need to take the minimum from making 5p (1), 4p (2) or 1p (1) and add on a coin to that, so that’s two coins, as you’d expect.

def numberofcoins4(amount, coins=[1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200]):

table = [float('inf')] * (amount + 1)

table[0] = 0

for value in range(1, amount + 1):

for coin in coins:

if coin <= value:

withCoin = table[value - coin]

if withCoin + 1 < table[value]:

table[value] = withCoin + 1

return table[amount]

So, we’ve a simple maths problem that we cover in Year 2 maths lessons, but taking this into computing, we can automate solving this, we can generalise this to a far broader class of problems, we can link this to binary (and other number base) conversion, we can get to grips with some tricky logical bugs, and apply sophisticated techniques like recursion and memorisation. From this example alone, I reckon it’s well worth making these connections between the maths curriculum and computing!

Originally published in Hello World 10

Share