Quad Blogging - reflections from children and teachers

Jul 02, 2014

In our ever-changing digital world, most children and young people are regularly in touch with each other through social media; whether is it is social networking sites, virtual worlds or online games operating via the World Wide Web. Social networking sites such as Facebook, Tumblr and Twitter allow young people to make links with friends and associates in their immediate circle and further afield. These sites often reflect a young person’s identity through the actual use of a particular site or the way they design their page (Dowdall, 2009). Researchers (Burke and Rowsell, 2008) have begun to explore these experiences and how such networking impacts on the networker’s communication practices. This online world has the potential to link young people to peers in their own country and even across the world. Other links occur for pupils who have family living in another part of their country or in another country. Such contact is also made through email, mobile phone apps and Skype. For the majority of pupils living in the EU and particularly in the UK, such digital contact is a regular part of their out-of-school lives. Creative Connections builds on these experiences through the Creative Connections website and the quad blogs created for pupils to respond to each other both through images and the written word in virtual settings.

Creative Connections Website: organisation and reflection

The Creative Connections project linked 25 schools from six different European countries. Each country’s school selection consisted of both primary and secondary situated in both rural and urban settings. To manage the visual and written word communication between the 25 schools five quad blogs and one quint blog were created. These were organised according to age phase. Thus there were three for primary and three for secondary. Each class could only read the postings from their own shared blog. The actual project lasted from January 2013 until the end of May 2013. Schools would work on a project and then post images and text about their work. Other pupils from either the other schools or their class would then write comments about these. To facilitate this communication automatic machine translation (Bing) was used for the blogging on the website. Whenever a post (image and some text) was uploaded a box (stating the default language) had to be ticked to identity the language that the post was written in. This then meant that any CC reader could click on a flag which denoted one of the five main languages of the project (Catalan, Czech, English, Finnish and Portuguese) and the text would be translated into that language. It was decided to use machine translation as translation by a human translator would be too expensive and introduce delays into the process of communication.

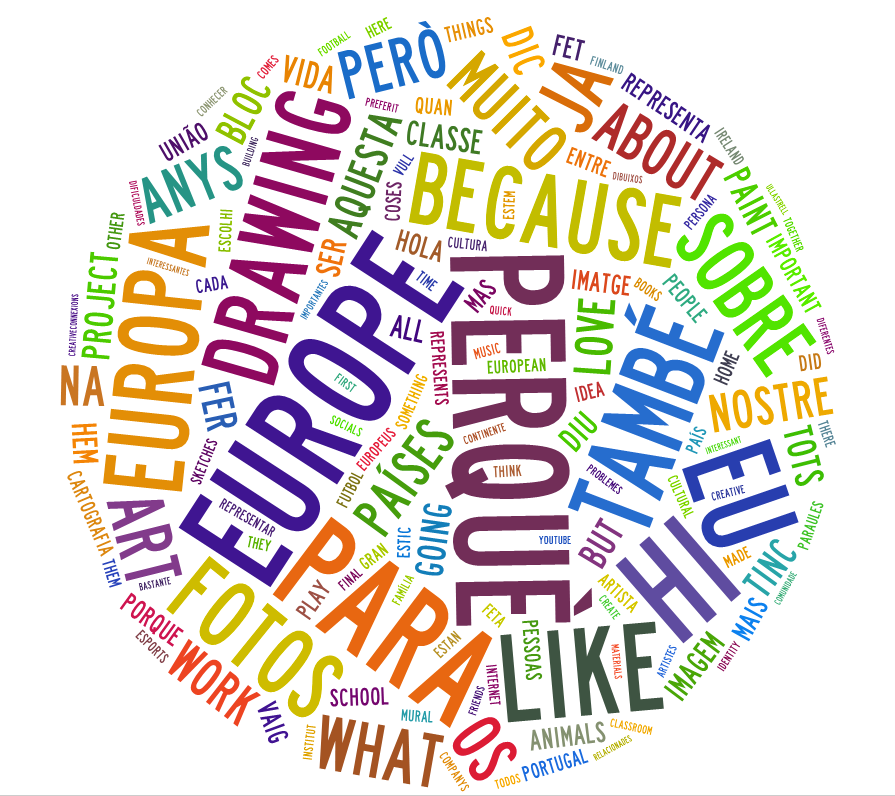

A total of 694 participants (children and teachers) had access to post comments within the quad and quint blogs. Over the course of the research phase (January-May 2013) a total of 961 posts across the six countries saw images, videos and text being uploaded to the gallery on the Creative Connections website. Pupils in Finland posted the most overall (n=253) and Czech pupils posted the fewest (n=51). An initial examination of the posts included creation of a Wordle diagram to begin assessing common terms and key words (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Wordle diagram assessing the Creative Connections Gallery Postings by pupils

The Wordle diagram includes words in all five languages and reveals common words such as Because, Why, Europe, Like – all components of the ways pupils described their works of art.

It should be noted that blogging generally did not happen throughout the course of the research phase. Rather, it typically became a part of the process once pupils had completed images and begun to post them and revealed patterns of response (usually influenced by access to computers and by age of pupils). Table 1 shows the number of comments posted by country and in Table 2, these data are explored to reveal the patterns of response between countries.

| Commenter | Czech | Finland | Ireland | Portugal | Spain | UK | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 27 | |

| Finland | 143 | 44 | 6 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 277 | |

| Ireland | 1 | 31 | 37 | 13 | 23 | 19 | 11 | 135 |

| Portugal | 18 | 35 | 51 | 35 | 6 | 1 | 146 | |

| Spain | 6 | 107 | 26 | 1 | 144 | 3 | 9 | 296 |

| UK | 1 | 191 | 69 | 47 | 33 | 269 | 84 | 714 |

| Other * | 31 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 51 | ||

| Total | 10 | 529 | 217 | 118 | 267 | 355 | 150 | 1646 |

* other = comments posted by researchers and teachers.

Table 1: Comments posted by participants (by country)

| Commenter | Czech | Finland | Ireland | Portugal | Spain | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech | 7% | 30% | 7% | 0% | 7% | 30% |

| Finland | 0% | 52% | 16% | 2% | 10% | 10% |

| Ireland | 1% | 23% | 27% | 10% | 17% | 14% |

| Portugal | 0% | 12% | 24% | 35% | 24% | 4% |

| Spain | 2% | 36% | 9% | 0% | 49% | 1% |

| UK | 0% | 27% | 10% | 7% | 5% | 40% |

Table 2: Percentage of original author’s countries (across) by commenter’s country (down)

Thus, whilst pupils were more likely to respond to work from other pupils in their class (i.e. in their own country), this was balanced by a generally good distribution of comments on posts from those from other countries, who would typically have written in another language. Pupils in some countries seemed more willing to engage in conversation than others, ranging from 0.3 comments per participant in Czech to 3 from participants in UK.

When the project had completed the research phase samples of the text was sent to a group of translators to assess the quality of the translations. Each of the five languages: Catalan, Czech, English, Finnish and Portuguese was assessed in relation to their translation into the other four languages. Translators were found for all the pairs except for Czech- Catalan, Czech – Portuguese and Portuguese – Czech. For these English was used as a pivot language.

Out of all the 20 translations a limited number of the translated texts were understandable but mainly the translators’ report found that the reader would understand the overall gist of the text but that the detail was missing. It was found that for most of the translations the vocabulary was good, as said by the translators: ‘well matched’ and ‘did well with the vocabulary’ and where there were issues with the vocabulary it was generally linked to errors made in the original by the pupils, spelling errors etc.

An example - from Finnish to Czech A Finnish pupil posted the question ‘Is the girl in the picture Romani?’ however the pupil misspelled Romani and wrote romaani, which means a novel in Finnish so the text was translated to ‘Is this a picture of a girl of the novel?’. This then is completely incorrect and would lead to multiple ‘mis-translations’.

The main errors which occurred in the machine translation were linked to grammar and syntax. Problems occurred because the Finnish language is complex and there were issues with morphology, inflection of nouns and the conjugation of verbs. The Czech language does not include articles so in the translation to Portuguese these were omitted. Sometimes the cohesion of the text was affected by the translation and interestingly the longer the text the easier it was to understand.

The corpora on which statistical machine translation is based are drawn from publicly available professionally translated works, typically official reports and minutes of international organisations such as the UN and European Commission (Zuckerman, 2013). The difference between such texts and pupils’ informal language in online discussion goes some way to explain the limited success of this technology here.

The responses from the pupils in the different countries varied. The UK pupils (particularly the younger pupils) were extremely positive about the automatic machine translation as they enjoyed being able to communicate with their European peers. The older Finnish pupils preferred to blog in English, as they were concerned that the machine translation would change their message. In contrast the Sami pupils in the north of Finland, who regularly speak three or more languages and in whose school these languages could all be heard, did not mind that the machine translation was often not perfect. The Finnish researcher commented: ‘The roughness of the translation didn’t bother them ‘.

Pupils’ reflections

On a general level, the pupils involved in the project were enthusiastic and excited about linking with their European peers. In the UK the younger age pupils enjoyed the fact they were connected and they could read other responses through the use of automatic machine translation. One UK ten year old said: ‘It is a very good project as you can be in touch with people you don’t even know and you know it’s safe’. The children also liked seeing each other’s art work and commented on how different the artwork was from country to country. One Irish school (4-12/13 years) found that a close link with a Spanish school through the Blog enhanced the children’s sense of being European as it helped them connect and identify similarities with their counterparts. Both sets of pupils saw similarities between their use of minority languages (Catalan and Gaelic) as well as developing discussions about pastimes, music, pets and football. As with other classes the children became excited when responses came through. However, in some schools the slowness of the responses was a disappointment for the pupils.

In one Czech school the pupils were not used to communicating with an unknown person they could not see, through either email or Skype, and the teacher said that the pupils had no idea about the tone of writing they should use and as a result a remark was posted, ‘I think you can be better’ which could have been seen as overly critical. In some schools in Ireland the pupils found writing responses to other’s work difficult as they were concerned if their comments might offend their blogging partners.

In one primary school in Finland an alternative way of using the website was organised, as the posting of students’ work was carried out by both the teacher and the researcher. Pupils were shown the artworks on the blog through a projector, they then jointly decided which image they wanted to respond to and what they would say. This discussion allowed for a more collaborative and deeper response about the artwork. The Sami school in the north of Finland wrote their posts in Finnish, Sami and English as the students were all multilingual and used to operating in more than one language. Another elementary school used the images to help them understand the machine translated text as one Portuguese school uploaded images of pigs being slaughtered and this was quite understandable for the children as reindeer are slaughtered as part of the Sami culture.

In relation to responses from secondary age pupils, some felt that the blogging made it more like a media lesson and others felt it would have worked better is all of the pupils were following the same scheme of work. They also felt it was a challenge to transmit to others the differences in their life styles and environment. One student asked for ‘an info page at the start of the blog with some facts and information about the classes in the blog’. Overall, secondary pupils tended to view this as a ‘school’ space and one which was familiar (i.e. similar to social networks) but not somewhere they would spend time unless it was part of a lesson. The issue of the ownership of online spaces is relevant here and this project demonstrates the importance of how young people ‘see’ these spaces and the ways in which their perceptions affect the level to which they are prepared to interact.

Teachers’ reflections

Feedback from the teachers in all countries was quite similar with regard to the process of setting up and engaging their pupils with the quad blogs. Overall, the research has revealed a constant concern regarding ability to use online resources, schools’ capacities to provide students with appropriate IT equipment, and the extent to which the use of IT could be integrated into art lessons. Teachers in all participating schools in the UK had similar issues when setting up and managing the blogging activities; the security required for online interactions is very strictly regulated in English schools and despite all children having their own login so they could manage uploading and communicating, it was common for teachers to do this for their pupils, as was the case in some Czech and Portuguese schools. Thus the potential for spontaneous interactions was limited. Two secondary teachers felt that their pupils considered blogging a chore and therefore not something that they ‘owned’ or engaged with. In one primary school there was one example of an exceptional child who blogged continuously, who posted images and ideas and was keen to communicate with peers in other countries.

In Ireland one teacher noted the connections made through the project as “hugely rewarding” and wished that this relationship could be maintained – this is also a goal for the overall project as maintaining these links is vital to the sustainability of the work. A primary teacher in a Sami school (Finland) explained that her pupils had little experience of online interactions and therefore the chance to participate in a project such as this was beneficial to both her and her pupils. In Spain, most of the schools engaged in the blogging, but one secondary class was particularly active in this regard and their teachers claimed they enjoyed spending time looking at the blogs and adding comments.

Commonly teachers found that the “talk” in lessons did not translate into the online environment; despite all teachers in all countries focusing on the use of rich questioning techniques, it was notable that pupils’ interactions online were minimal, often unfocused or irrelevant. In Finland, a teacher noted that most responses were “shallow” for example “that looks nice” and she wished, as did her colleagues in Portugal, that they had more time for developing blogging skills. However, one unique example was the ways in which an Irish teacher felt her pupils had developed stronger “empathy with their counterparts” due to use of ‘minority’ languages (Catalan and Gaelic). These strong connections were vital and the Finnish teachers (secondary level) felt that seeing other pupils’ faces would improve the blogging connections as this was, she argued just “communicating with a computer” and being able to see their peers may have engaged pupils to a greater degree.

Problems with uploading, using the website and encouraging pupils to blog were mentioned by all participants; some teachers admitted they had been anxious about logging on and experimenting with the website. There was also evidence of teachers having to manage the ‘content’ of blog posts – so whilst pupils had to wait for a teacher to ‘okay’ their submissions, this led to delays, some disinterest and lack of engagement. A key recommendation for blogging between countries will be to tailor the timing carefully so that pupils know they will have a response within a certain time as teachers noted that the excitement of posting images quickly diminished when there were no responses. This kind of planning will be labour-intensive for teachers planning these kinds of connections, but careful organisation should enhance the online experience for participants.

Practical Issues

It would have been beneficial for all schools to have made a visual introduction of themselves in the form of a photographic representation or film. Some schools did do this, but others did not and this meant that a tangible ‘connection’ was missing. It is possible that an on-screen meeting would help pupils to visualise their partners and to give them a more realistic sense of audience.

Written posts needed to be checked for spelling and grammar errors before being posted as these errors interfere with the translation into another language.

Forgetting to select the default language button when teachers were uploading information meant that the machine translation did not function correctly.

In some countries the teachers’ nervousness of the technology impacted on the links with other schools; they were reluctant to share information and communicate online due to a lack of confidence in using this new environment.

Working between countries is problematic due to time issues – when schools try quad blogging in future, we suggest that schools work out a ‘rota’ for engaging in blogging so that they can guarantee regular interactions.

Ethical issues

During the duration of the project a small number of ethical concerns were raised both by the research team and a few teachers. The first issue linked to an initial posting by a ten year UK boy. Thomas uploaded a self-made poster during the February holiday about paint balling, which included an image of a pistol at the top, as can be seen in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Thomas’ poster

The UK research team removed the image from the website as they felt such an image should not be shown. Thomas, when interviewed, said he had not deliberately included this image instead of an image of a proper paintball gun. Another ethical issue occurred when Spanish pupils posted a video clip from a popular TV show which pupils in one of the UK secondary schools did not like; their complaints led to it being removed from the gallery. Two other ethical issues arose because of confusion over language, one with a mistranslation of a Catalan word into a swear word and the other through an English teacher misinterpreting a comment from Czech pupil.

Recommendations

- Children should experience discussing artworks in groups and as a whole class, and at the beginning of the project teachers might need support in how to engage pupils in responding to artworks.

- Teachers should model how to respond to artworks to emphasise thoughtfulness and constructive criticism.

- Teachers should encourage inter-country dialogue, acknowledging pupils’ enthusiasm for this aspect.

- In future projects careful consideration should be given to timings and pace of the project, so that all partners are uploading work and posting comments within a specified time frame.

- One broad theme which is jointly decided between the members of each quad blog would give a sense of purpose and direction for the responses by the pupils.

- Teachers need on-going training to develop their confidence and skills in using digital technology.

- Teachers might need support in organising the use of digital facilities.

- In the light of teachers’ inexperience use of technology in their teaching, the processes on the website needs to be simplified for blogging, the posting of images/comments and for searching in the blogs.

- Teachers should allow the pupils to use the safe environment of the quad blog independently or in their home.

- In some countries, where technology is less integrated into the curriculum, more support is required for teachers in the use of the digital processes.

This research presents tentative explorations of blogging between countries and in multiple languages and it suggests that this could be useful way of creating connections between schools, teachers and pupils. It is important to note, as we always have, that [we might see] “…blogging as a way of supporting a community of practice or an affinity space… Blogs in and of themselves, do not necessarily promote social participation” Davies and Merchant (2009).

Useful reading

Burke, A. & Rowsell, J. (2008) ‘Screen Pedagogy: Challenging Perceptions of Digital Reading Practice’ Changing English, Vol.15, No. 4: 445 — 456

Carrington, V. and M. Robinson (eds) Digital Literacies: Social Learning and Classroom Practices London: Sage

Dowdall, C. (2009) Masters and critics: children as producers of online digital texts in Carrington, V. and M. Robinson (eds) Digital Literacies: Social Learning and Classroom Practices London: Sage

Davies, J. and Merchant, G. (2009) ‘Negotiating the blogosphere: educational possibilities’ in Carrington, V. and M. Robinson (eds) Digital Literacies: Social Learning and Classroom Practices London: Sage

Zuckerman, E. (2013) Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection, London: W. W. Norton and Co.

Originally published in the Creative Connections project digital catalogue. EACEA-517844 An EU funded Comenius Project

Share