Papert, turtles and creativity

Jan 18, 2015

Computer science as an entitlement for all as part of the national curriculum is undoubtedly an achievement of which CAS and its friends can be proud. It’s appropriate that our attention now moves from the ‘what’ to the ‘how’ of computing education. We would, though, be wrong to think that this is all entirely new: programming has been on the national curriculum since its very beginning in 1989, and school children have been learning to program in Logo since well before that.

Much of the very early work on teaching children to program was due to the influence of one man, Seymour Paper. Papert’s insights into both the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ of school computer science education seem to many of us as fresh and as relevant as ever, and I’d like to explore just a few aspects of this legacy here.

Born in South Africa in 1928, Papert’s childhood included plenty of ‘tinkering’ with cogs and gears, providing some early concrete experience of mathematical concepts. Papert studied maths at university before spending time working with Jean Piaget in Geneva. He worked in AI research at MIT’s AI lab alongside such heroes as Marvin Minsky and John McCarthy (inventor of Lisp). It was there, in 1967, that Papert and others created the first version of Logo, as well as the first physical floor turtle robots which it would be used to program.

In Mindstorms (1980), Papert writes eloquently about his vision:

In many schools today, the phrase “computer-aided instruction” means making the computer teach the child. One might say the computer is being used to program the child. In my vision, the child programs the computer and, in doing so, both acquires a sense of mastery over a piece of the most modern and powerful technology and establishes an intimate contact with some of the deepest ideas from science, from mathematics, and from the art of intellectual model building.

This pretty much set out the agenda for what CAS has achieved, moving pupils from being consumers of digital content, albeit interactive, well designed educational materials, to their taking charge of computers through writing their own programs: not as an end in itself, but rather because through this they would come to understand the world better.

Papert writes about ‘powerful ideas’, such as geometry and the laws of motion, which once grasped change the way a child will look at the world around them. Papert argues that programming helps children grasp these far more directly than other approaches, I think because programming makes these models themselves, or ‘microworlds’ as Papert described them, something which a child can create, adapt and explore. This is a big part of what national curriculum computing is setting out to do: ‘to use computational thinking and creativity to understand and change the world’. Interestingly, whilst Jeanette Wing deserves much of the credit for popularising ‘computational thinking’, the term was coined by Papert back in 1996, in relation to just this sort of powerful abstraction and exploratory ‘tinkering’. It’s important to recognise that coding is a means to this end, not an end in itself.

The Logo programming language is probably best known for its implementation of turtle graphics. The turtle was originally a simple robot, able to move forward and backward a set number of steps, or turn left or right through an angle, drawing as it moves. This still seems a highly effective way to introduce pupils to programming (think Roamer Too or Pro-Bot), not least because it’s so much easier to use logical reasoning to predict and debug Logo programs when you can literally put yourself in the place of the turtle, following the same instructions as the robot follows. Later on, the turtle became an on-screen representation, able to follow the same programs as the floor turtle would. The Logo language also includes constructs for repetition, variables, selection and, crucially, procedures and functions. It would certainly suffice for meeting the national curriculum programming requirements at Key Stage 2 and those for a text based language at Key Stage 3, although it’s certainly not as popular as a first teaching language as it once was. There are plenty of Logo interpreters around for most operating systems: I’ve a soft spot for Joshua Bell’s browser based javascript version.

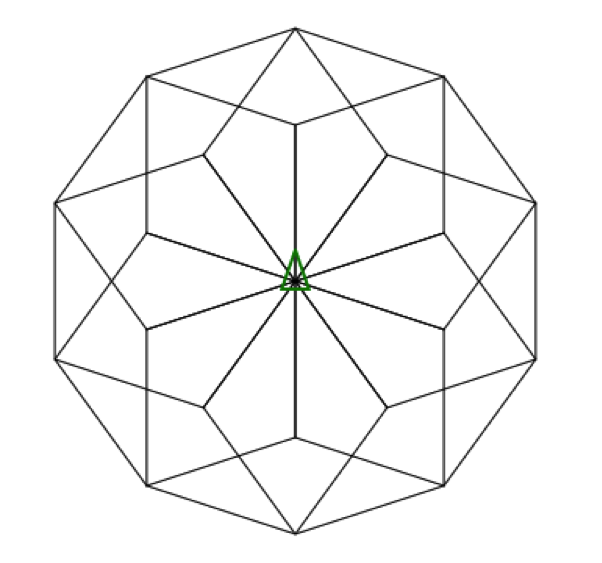

Logo’s turtle graphics provides a great way in to the language. Children can experiment to find a way to draw familiar geometric shapes (squares, then equilateral triangles, then regular pentagons and so on), their own pictures (remembering the importance of creativity in computing), or more complex geometric figures, such as the ‘crystal flowers’ of the old QCA schemes of work.

repeat 10 [

repeat 5 [

fd 100

rt 72

]

rt 36

]

Through experimenting with turtle graphics programs like this, children can develop a better feel for geometry, discovering for themselves that 360° makes a full turn, the exterior angles of regular polygons, and so on, as well as some aesthetic appreciation of geometric beauty.

Papert writes about the importance of user-defined procedures in Logo, not merely as a convenient programming construct for decomposing complex problems, but, drawing perhaps on his background in AI research, as a means for a child to learn more about learning, as the child teaches the computer a new word, defining that using the words already in its language.

to square :length

repeat 4 [ fd :length rt 90 ]

end

Logo also supports functions and recursion, and indeed could be used as an introduction to functional programming:

to factorial :number

if :number = 1 [output 1]

output :number * factorial :number - 1

end

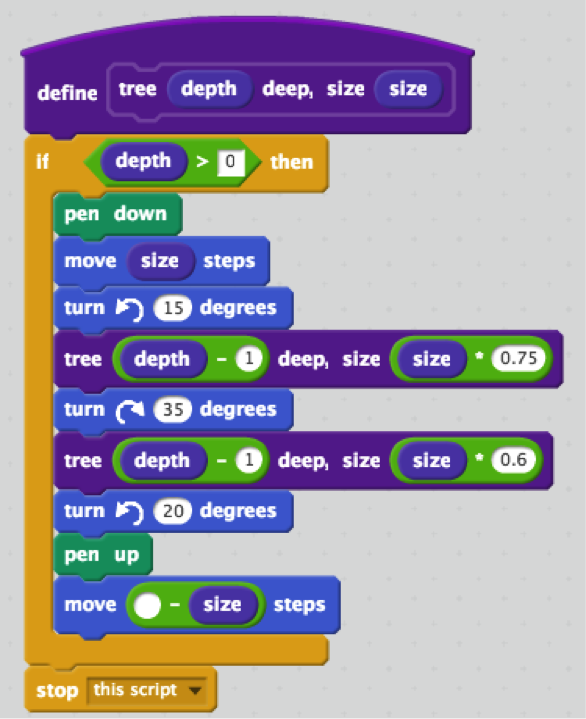

Given the ‘powerful ideas’ that turtle graphics provides access to, it’s not surprising that it’s been incorporated into so many of the programming languages used in schools. Scratch has a good implementation and the building block approach helps reduce the cognitive load of remembering commands and punctuation. User-defined procedures only came to Scratch in version 2, which is surprising given Papert was Mitch Resnick’s PhD supervisor. There are good turtle graphics libraries for Python, Small Basic and Touch Develop: I think moving from Scratch to one of these text-based languages is all the easier if pupils can see the connections between their Scratch scripts and their text based programs:

def tree(turtle, depth, size):

if depth > 0:

turtle.pendown()

turtle.forward(size)

turtle.left(15)

tree(turtle, depth-1, size*0.75)

turtle.right(35)

tree(turtle, depth-1, size*0.6)

turtle.left(20)

turtle.penup()

turtle.backward(size)

Lovely as turtle graphics are, there’s so much more to Logo than just this. One of Papert’s early papers (1971!) discusses using Logo to make a drill and practice maths quiz, in much the same way as we might get Year 4 to use Scratch to make this sort of ‘educational game’ now:. He observed:

I have seen children for whom doing arithmetic would have been utterly boring and alienated become passionately involved in writing programs to teach arithmetic and in the pros and cons of criticisms of one another’s programs

Brian Harvey’s excellent Computer Science Logo Style: Symbolic Computing (1997), once used for undergraduate CS at Berkeley, focusses on natural language processing in Logo instead of turtle graphics. I suspect part of the reason why Logo programming in schools back in the 80s failed to live up to its promise was that Logo became so closely associated with turtle graphics and maths education that it’s potential as a general purpose programming language largely went unnoticed. Looking back in 2001, Richard Noss and others remarked:

Logo was marginalised, remoulded as harmless to the mainstream educational system, redrawn as “a drawing tool” rather than as any kind of catalyst for rethinking the content of what is or what needs to be taught.

I do hope our renaissance of programming in schools doesn’t suffer a similar fate this time round.

Just as there’s far more to Logo than turtle graphics, so there’s much more to Papert’s work than Logo. His notion of ‘constructionism’ as a learning theory is at least as enduring as his work on Logo. Constructionism starts with Piaget’s constructivism in that it sees learning as the about each learner building and refining mental models of how the world works. Piaget saw learners as lone scientists, developing their understanding through discovery, exploration and experiment, Papert sees learners rather as designers or engineers, recognising that the best way to develop these mental models is often through the process of building real models, sharable, public artefacts which embody something of that emergent understanding: thus children write code not merely so we can assess their computational thinking but because it’s through the process of writing code that computational thinking best develops. The sort of design and engineering processes that lie at the heart of Papert’s concept of learning through making recognise the importance of pupils’ own creativity in computing, and the rest of the curriculum.

Another theme that recurs throughout much of Papert’s writing, and many of the YouTube clips of him talking, is ‘passion’, or even ‘love’. Whilst these aren’t comfortable words to use about schooling today, I think we can acknowledge that developing a love of knowledge, and a love of learning is something teachers and schools ought to do, even if this didn’t make it onto the aims for the national curriculum. How can computing teachers best do that? Partly through allowing pupils to find something of the joy of creating code, but also through passing on something of their own passion: both for their subject and for learning itself.

Originally published as ‘Seymour Papert’s Mindstorms. The powerful ideas that lie behind Logo’ in the Spring/Summer 2015 edition of Switched On, the Computing at School magazine.

Share