Coding across the primary curriculum

Jul 25, 2016

Quite recently, we thought the future of ICT education would be one in which technology was embedded seamlessly throughout all aspects of teaching and learning, and that all a child could possibly need to learn about IT could be taught within the context of other subject areas. The seamless embedding of technology throughout the life of a school remains a dream for many, but schools at the cutting edge have already achieved much with 1:1 devices, robust wifi, great training and a vision for how technology can transform education.

On the other hand, few would now argue that we can teach the new computing curriculum without setting aside some dedicated time to mastering the content of this new foundation subject. In the move from ICT to computing, our focus shifted away from the skills of using technology to knowledge and understanding of the principles of information and computation. It seems that mastering the foundational ideas of computer science, and particularly programming, requires some dedicated curriculum time. That’s not to say though that computing should be taught in isolation: the other subjects can provide motivating, relevant contexts for pupils to apply their computational thinking and programming skills.

Computational thinking

Computational thinking is the golden thread running through the computing curriculum: this is about looking at problems in such a way that a computer can help us solve them. It draws together such concepts as logical reasoning, decomposition, patterns, abstraction and algorithms, as well as approaches such as tinkering, making, debugging, persevering and collaborating.

The foundations of computational thinking are laid in EYFS’s characteristics of effective learning, but these concepts and approaches can be applied to any area of the primary curriculum further up the school: following or writing instructions makes use of algorithmic thinking; doing corrections in maths is debugging; looking for explanations in science is logical reasoning, and so on. As pupils become better at computational thinking through computing lessons, they’ll be better able to apply this across the curriculum.

I think we can go further than this though. As pupils have been getting better at programming, I think we’re reaching the point where they can start to use this to do some creative things in other subjects. This isn’t merely about using other subjects as a context for learning to code, this is about coding as a way to help pupils learn in other subjects too. Here are some examples:

Maths

The relationship between maths and programming goes back to Alan Turing and the the foundations of computer science. Simple turtle graphics are a great way to help pupils get a far more visceral feel for geometry, as they put themselves in the place of the turtle. Pupils quickly learn for themselves that exterior angles sum to 360˚. Writing programs where sprites move around the screen in Scratch similarly makes coordinates and negative numbers seem more real and more useful.

In maths, we make use of algorithms (sequences of steps and sets of rules) all the time. We’ll teach pupils algorithms for checking if a number is prime, for finding common factors or for doing arithmetic with fractions. With a few coding skills, pupils could put their knowledge of these to the test by writing their own programs to implement these rules, trying them out with much bigger numbers than the exercises we set, and perhaps even finding faster algorithms for the same problem.

Music

Scratch has music making tools built in – it’s easy enough to record and play back audio, but it’s well worth getting pupils to experiment with creating music by sequencing notes and their durations. There’s a range of instrument and percussion available, and it’s possible to play multiple notes at the same time, so pupils can experiment with chords and polyphony. Repetition in programming can be linked to music compositions too, and pupils can explore randomly generated music, or music that reacts to input from mouse, keyboard or sensors. Pupils can improve their compositions in the same way as they debug their programs.

Beyond Scratch, Sonic Pi and EarSketch take the text-based, grown-up programming languages Ruby and Python and make them directly applicable to musical composition. They’re certainly accessible to upper primary pupils, but go way beyond that level. There’s some amazing work going on at the moment at the intersection between music and computer science.

use_bpm 90

use_synth :pretty_bell

define :sequence1 do

play_pattern_timed [:e,:e,:f,:g], [0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5]

play_pattern_timed [:g,:f,:e,:d], [0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5]

play_pattern_timed [:c,:c,:d,:e], [0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5]

end

sequence1

play_pattern_timed [:e,:d,:d], [0.75,0.25,1]

sequence1

play_pattern_timed [:d,:c,:c], [0.75,0.25,1]

play_pattern_timed [:d,:d,:e,:c], [0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5]

play_pattern_timed [:d,:e,:f,:e,:c], [0.5,0.25,0.25,0.5,0.5]

play_pattern_timed [:d,:e,:f,:e,:d], [0.5,0.25,0.25,0.5,0.5]

play_pattern_timed [:c,:d,:g3], [0.5,0.25,1]

sequence1

play_pattern_timed [:d,:c,:c], [0.75,0.25,1]

D&T

There’s an expectation in the Design and Technology curriculum that pupils at Key Stage 2 will

“apply their understanding of computing to program, monitor and control their products.”

Platforms such as the Lego WeDo, Crumble and the BBC micro:bit make it much easier than ever before for pupils to take their first steps into the realm of ‘physical computing’, using buttons, switches and sensors to accept input, writing their own code to process this and producing output through LEDs, speakers and motors. Whilst the BBC micro:bit’s initial distribution was to secondary schools, the online editor and emulator is accessible to all at microbit.co.uk.

The most exciting work in physical computing, at school and beyond, is happening on the Raspberry Pi: which has a set of general purpose input and output pins built in, and support for using these from its own version of Scratch. There’s a ‘sense hat’ too, which incorporates a tiny display, joystick and some sensors: a couple of these, with programs written by British school children, went up to the international space station with Tim Peake for the Astro Pi.

Art

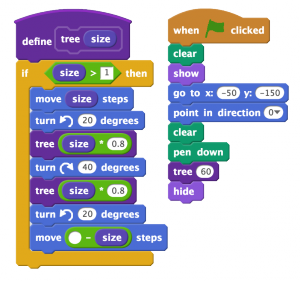

Turtle graphics in Scratch, Logo or Python needn’t be restricted to maths – there’s ample scope to use this as a medium for pupils creative work in art too. QCA’s old scheme of work for ICT had a lovely unit on crystal flowers, there’s plenty of scope to explore tessellating patterns and Islamic art has a rich history of beautiful, geometric art to provide inspiration here. There’s also scope for exploring more natural patterns, experimenting with simple code to create recursive fractals for trees, fern leaves, broccoli or coastlines.

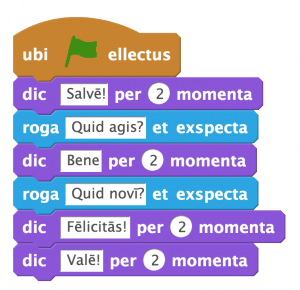

Foreign languages

Scratch has excellent support for working in foreign languages – the familiar English of the programming blocks can be replaced with keywords from many other languages, even including Latin. This is great for pupils learning English as an additional language, but is also a nice way to build up pupils’ familiarity with a foreign language. Scratch is great for producing short, scripted animations, with on-screen and recorded dialogue or narration: why not have pupils program animations for a language they’re learning, or even a simple chatbot?

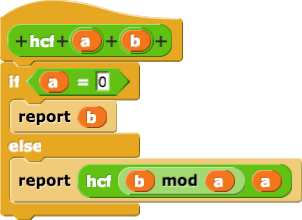

You can also program Scratch (or Python) to generate semi-random, but grammatically correct sentences, using the computer science idea of a finite state machine. Playing with this gives some insights into the structure of a language: you could do this for English, but also for any other language that pupils are learning.

Looking for ways for pupils to use their IT skills across the curriculum, such as searching for information, making presentations and editing videos, remains as valuable as ever. Alongside this, I think we should now start looking for some of the cross-curricular ways that pupils can use their programming skills too.

Originally published in Teach Primary, June 2016. © all rights reserved. I explored these ideas further, with reference to the secondary curriculum, in my plenary at #casconf16:

Share