Compuitng in English Schools

Oct 31, 2016

In September 2014 England replaced its old ICT curriculum, which had a focus on building skills using a range of software tools, with a new subject, ‘computing’, that included significant elements of computer science for pupils from age five to 16, including an expectation that even our youngest pupils would learn to write their own simple programs. Whilst it’s still early days, the indications are that the change has been largely successful, with pupils enjoying the challenge of the new subject, most teachers feeling confident teaching computing and a significant rise in the numbers of students taking qualifications in computing at 16+.

Rationales

Why should we teach computer science to children? I think it’s possible to give a number of rationales for this.

I’m sure that for ministers, the main argument is an economic one: to sustain or develop vibrant technology sectors requires a stream of computer science graduates, and a firm foundation in computing at school level helps ensure this. This makes sense at individual level too: software engineering is a meritocratic field, and learning to program can do much to promote social mobility.

However, school is perhaps too early for vocational training for the software industries. We don’t teach poetry or music in schools because we need more professional poets or musicians, but because these fields provide unique insights into human experience and great scope for pupils’ creative expressions: the same is true of programming. Given the role of digital technology in our lives and society, some understanding of the principles on which it is built should be an entitlement for all. More than that, whilst still a relatively new field, computer science like the natural sciences as providing insights into the nature of reality: for example, some problems are easy, some are impossible, some are hard and some are hard unless we think about them the right way.

There’s also an argument that learning to program helps develop a particular way of thinking, of looking at problems or systems in such a way that a computer can help us solve or understand them. As Seymour Papert wrote back in 1980,

I began to see how children who had learned to program computers could use very concrete computer models to think about thinking and to learn about learning and in doing so, enhance their powers as psychologists and as epistemologists.

From ICT to Computing

England’s journey from ICT to Computing was a rapid one. As recently as 2009, proposed changes to the ICT curriculum emphasised the need for pupils to use and apply ICT skills in their learning and everyday contexts, and to become independent and discerning users of technology: no one would argue that these are bad things, but the ambition here seems, in retrospect, somewhat limited.

In 2010, the Royal Society began a review the state of computing education, taking a view that curricula should ensure students could engineer technology rather than merely consume it. Ian Livingstone and Alex Hope, key figures in Britain’s games and visual effects industries, recommended that computer science be brought into our national curriculum as an essential discipline to ensure the long term success of their industries. Google’s Eric Schmidt used his speech at the 2011 Edinburgh Television Festival to express surprise that we weren’t teaching CS in schools and thus risked throwing away our ‘great computing heritage’. England’s education inspectorate and the commission reviewing our national curriculum also were critical of the then state of ICT education.

In light of these views, the then education minister Michael Gove announced in January 2012 that the old ICT curriculum would be ‘disapplied’, allowing schools the freedom to introduce more computer science themselves. Subsequently he announced that an expert panel would be convened under British Computer Society / Royal Academy of Engineering chairmanship to develop a new curriculum, drawing its membership from industry, academia and schools.

Curriculum content

The computing curriculum developed by the panel, and subsequently revised through public consultation, recognised that computing as a school subject had three elements: computer science, information technology and digital literacy. It’s helpful to think of these as the foundations, applications and implications of computing, respectively. Important as computer science is, as the core of computing, it’s still necessary that children leave school being able to find information, develop content for the web, edit video and so on. It’s also vital that they can think through the ethical implications of technologies and consider their own moral responsibility when working with digital technology.

The new programmes of study for computing set out an ambitious vision:

A high-quality computing education equips pupils to use computational thinking and creativity to understand and change the world.

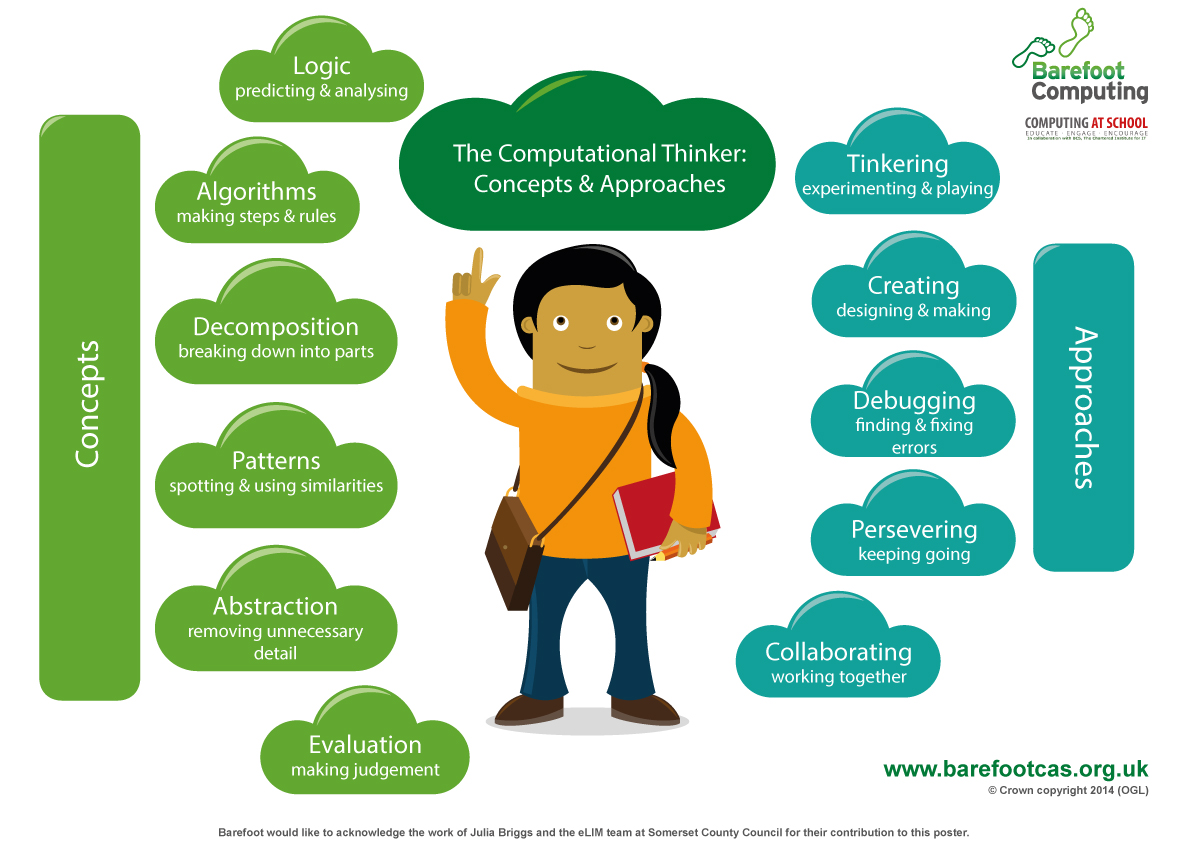

Creativity characterised much of pupils’ work under the old ICT curriculum, and remains central to computing. Computational thinking is a golden thread running throughout the new curriculum. It includes concepts such as logical reasoning, algorithms, abstraction, decomposition and generalisation which are central to programming, but also to the much more general use of computers to solve problems and get useful things done. Computational thinking also encompasses a range of approaches, the ways of working common to software engineering, but certainly not limited to this domain. These include tinkering, making, debugging, persevering and collaborating: good computing education needs to develop pupils’ capabilities here as well as their grasp of the underpinning concepts.

The foundations of computational thinking are laid even before pupils start formal education. Our guidance for pre-school education includes developing ‘characteristics of effective learning’, which include ‘finding ways to solve problems’, ‘testing ideas’, and ‘planning, making decisions about how to approach a task, solve a problem and reach a goal’. These are all part of pupils’ everyday experience in pre-school, but are also characteristics of software engineers at Google, Microsoft and Facebook.

For five to seven year olds, the new curriculum includes an expectation that pupils should understand what an algorithm is, as well as how algorithms are implemented on digital devices (which are as likely to be floor robots or iPads as laptops or desktops at this age). Pupils learn to create and debug programs, as well as reasoning about what a program will do - this latter is crucial. They also use technology to create and manipulate digital content, as well as learning the basics of online safety, including privacy.

Seven to 11 year olds build on this, including sequence, selection, repetition and variables in their programs, and using logical reasoning to debug their algorithms or programs. In most schools, the Scratch toolkit from MIT proves well suited to these requirements. Pupils learn about how the internet, the web and search engines work. They’re expected to select software to accomplish goals, to design systems and content, and to analyse and evaluate both data and information. The digital literacy expectations include pupils taking responsibility for their actions.

Between 11 and 14, the expectations are greater still, including the design of computational abstractions, the use of more complex data structures such as lists or arrays, and functions or procedures in their code. There’s an expectation that pupils will learn at least one text-based programming language at this stage: Python seems to be the popular choice. Some of the underpinning theory of CS is covered here too, including classic algorithms for search and sort, the fetch-decode-execute cycle, Boolean logic and binary arithmetic. There’s an expectation that pupils engage in creative projects, including remixing content created and licensed by others. Digital literacy recognises the importance of security, identity and privacy.

From 14 to 16, there’s a minimum statutory entitlement for computing, phrased in such a way that schools could embed this in cross-curricular provision, but there’s also an expectation that students should be able to opt-in to a more demanding specialist curriculum leading to a rigorous, academic qualification in computer science. The requirements for these qualifications include material on how computers and programs work, questions on computational thinking and a practical programming project conducted in response to a detailed, unseen brief under closely supervised conditions.

Between 16 and 18, computer science is one of a portfolio of courses which students can elect to study. New specifications are in place emphasising the academic rigour of these qualifications, including topics ranging from working with big data to functional programming. The project work here is much more open ended, with students choosing for themselves a software product to develop or an area to investigate independently. These elective courses are seen as good preparation, not just for computer science degrees but also for degree courses in social and natural sciences, medicine, engineering and mathematics.

Implementation

To change the curriculum in this way needed changes in statutory regulation, but beyond that government has largely stepped back from implementing the change, taking the view that ‘government should only do what only government can do.’ Thus the specifics of implementing the new curriculum have largely been left to teachers, local authorities, publishers and not-for-profit organisations. Fortunately, England has evolved a vibrant, multi-layered ecosystem supporting pupils and teachers in this domain. A few initiatives deserve specific mention:

Computing At School (CAS)

CAS is a membership association of teachers and others keen to promote and support computer science teaching for all. It has over 23,000 members, and has led many of the initiatives to see computing established in schools. CAS has built up a network of teaching excellence in computer science education, including some 400 or so ‘master teachers’, lead schools and regional university partners. CAS has developed professional development programmes for primary and secondary teachers, including Barefoot Computing and Quickstart Computing. There’s also a vibrant online community with a culture of sharing resources.

Raspberry Pi

The UK’s most successful computer, the $35, Linux powered Raspberry Pi, was developed with the purpose of providing a platform on which young people can experiment with programming, networking and control. All profits from sales of the Pi go to support the Raspberry Pi Foundation, whose mission is to ‘put the power of digital making into the hands of people all over the world.’ The foundation produces some very high quality teaching materials and resources, and runs the innovative Picademy professional development programme. The foundation merged last year with Code Club, who run after-school coding clubs for pupils aged 9-11 as well as a professional development programme for primary teachers. Their teaching resources are also freely available online.

BBC Make It Digital

The UK national broadcaster, the BBC, ran a year long initiative including broadcast and online content to support coding and other aspects of digital making. As part of this, the BBC with 29 partner organisations put a micro-controller based device, the BBC micro:bit into the hands of every eleven year old in the country, with the aim that this would inspire a new generation of digital makers. The micro:bit has a 25 pixel (!) LED display, a couple of input buttons, input/output connectors, accelerometer and Bluetooth connectivity. It can be programmed online in Javascript, Blockly, TouchDevelop and Python.

There are many other organisations that have played a key role in helping to establish computing as a curriculum subject. There’s been generous support from Microsoft, Google and ARM, some great work from universities, such as Michael Kölling’s Greenfoot Java environment developed at the University of Kent and Paul Curzon’s CS4FN project at Queen Mary University of London, and mainstream education publishers including Rising Stars and Hodder Education.

It would be wrong to leave the impression that England has all this sorted already. There’s plenty more on the agenda, including delivering a genuinely inclusive entitlement to computing for all; ensuring that computing is taught, and taught well, in all schools; a need to research what makes for effective pedagogy in computing at school; attention to the transition from primary to secondary; and developments around how computing can best be assessed, both formatively and summatively. The journey from ICT to computing has been an exciting one, but the road ahead looks even more interesting.

Originally published in a special edition of Schule Aktiv © all rights reserved.

Share