Computational thinking and problem solving

Sep 24, 2018

Computational thinking is something that everybody can do, and that you can integrate into your classroom.

Programmers and computer scientists have their own particular way of looking at problems. We call this computational thinking, and this is something you can easily teach to your students. As they get better at thinking like this, don’t be surprised if they get a lot better at coding, and perhaps at other sorts of problem solving too…

But what is computational thinking? Computational thinking is a way of looking at problems so that computers can help us solve them. When your students are programming, computational thinking covers the problem solving they have to do before they can start coding: working out the steps or rules to follow, figuring out how states and behaviors are represented, and thinking through how their program will interact with its user, or other systems are all part of computational thinking. In school, it can be helpful to think about some of the common elements of computational thinking. For example:

- logical reasoning: encourage your students to make predictions and give explanations, whether or not they are working with computers;

- decomposition: helps students to break big problems down into smaller parts, whether they are working on their own or as part of a team;

- generalization: get your students looking for patterns, or thinking about similar problems;

- algorithms: a key to computational thinking is working systematically: what steps or rules do you have to follow?

- and abstraction: what is the right level of detail for the problem? What information matters? What is irrelevant, at least for the time being?

Games can be a great way to help your pupils to think computationally. Games have objectives, they have rules, they have some way of representing the state of the play, so it’s perhaps no surprise that people have been programming computers to play games for a very long time now. You don’t have to use computational thinking to just play a game, although these approaches can sometimes help you win, but you do need to use computational thinking if you want to program a computer to play!

Let’s take a really simple game as an example. It might be one you’ve already played with your students in their maths lessons. I call it “Guess my Number”. The objective is to guess the teacher’s number. The rules say you can only ask yes/no binary questions. You can think of the state of the game as what numbers might still be possible answers.

Do try it with your students! You can play the game even with very young children, as long as you limit the possible numbers to ones they’re familiar with, perhaps just starting with whole numbers from 1 to 10 or 1 to 20. In a maths lesson, it’s a great way to develop children’s mathematical reasoning and their familiarity with the number line. In a computing lesson though, we’re less interested in just winning the game “Guessing the Number”, than coming up with a systematic way to play the game that we could program into a computer, so it’s worth stepping back from playing, to do a bit of thinking. What approach might you program a computer to take here?

One algorithm is just random guessing. Keep picking possible numbers, perhaps avoiding those you’ve already checked, until you hit the right one: is it 37? Is it 51? Is it 109? And so on. Slow, and really tricky to keep track, but it’s still an algorithm.

Another might be linear search: start at the beginning and keep going, one at a time, until you get there: Is it 0? Is it 1? Is it 2? And so on. Still slow, but our abstraction is much easier, we just need to remember what we checked last, and somehow this seems more systematic.

Much better, much faster is to use a “divide and conquer” pattern. Let’s say I tell you my number’s between 0 and 127. Your first question could be “Is it 64 or more?”, I say “No”. So now you know it’s between 0 and 63. Then you ask, “Is it 32 or more?” I say “Yes”, so you know it’s between 32 and 63. Then you ask, “Is it 48 or more?” I say “No”, so you know it is between 32 and 47, and so on.

Your abstraction is just the range you’re left with at each stage, and your algorithm is to pick the mid-point and ask whether it’s there or more. You’ve broken down the original problem into a sequence of progressively smaller and smaller problems until there’s only one number left, and you can apply the same pattern at each stage.

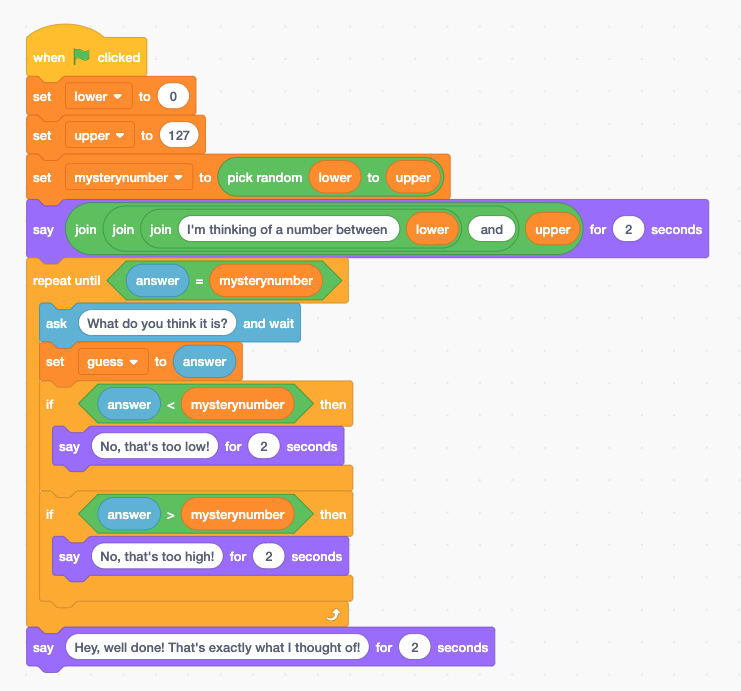

Let me just show you what this approach would look like as Scratch code. Notice we’re keeping track of the lower and upper limits, as we go round this repeating loop until there’s only one number left. Each guess the program has, it has to adjust either the lower or the upper limit, depending on the answer it gets.

It’s worth saying that we can generalize this particular approach - why stop at 127? Why not go up to 1023 or 1,048,575? Or perhaps guessing words?

You could play the game of “20 Questions” in any subject: perhaps guessing towns or cities in geography, or animals and plants in biology lessons - this binary search approach is very similar to the classification keys that botanists and zoologists use for identifying plants and animals in the wild.

More generally still: this ‘divide and conquer’ approach is used by computer scientists to solve all sorts of big problems, systematically reducing them to a sequence of smaller and smaller sub-problems - as your students do more coding, they’ll see this again and again!

You can teach a lesson based on this idea with lots of different age groups: with young children, just play the game! With slightly older ones, get them to think about how they could play the game systematically. With older pupils, they could code this game, whether in Scratch or Python or some other language. Or perhaps they could experiment with coding their own version of ‘20 Questions’ for animals, plants or any other category! You will find below other lesson plans that will help you get started with helping your students to think computationally.

Now that you know that computational thinking is not that difficult, why not try an activity with your students?

Originally produced as a video for EU Codeweek

Share