Learning languages with Scratch

Jan 15, 2019

Lots of educational software follows essentially the same algorithm, which might not be that different from what teachers have done in their lessons: Repeat until you’ve asked enough questions:

Ask a question

Get a response

If the response is right:

Say ‘well done’

Else:

Say ‘no, think again’.

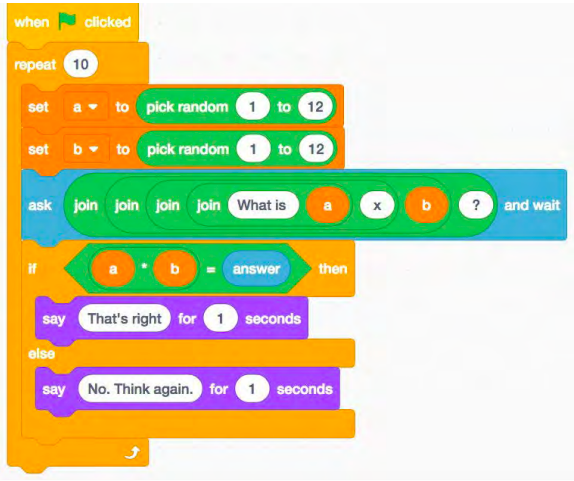

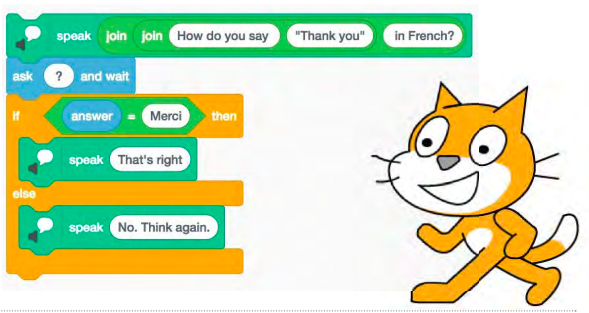

It’s a nice programming challenge to try to write something similar in Scratch, perhaps with pre-made questions, or using the random number block to generate questions automatically:

One of the lovely things about this simple program is that it uses sequence, selection, repetition, variables, input and output - all the constructs needed for the programming requirements of the English computing curriculum, making it a great example.

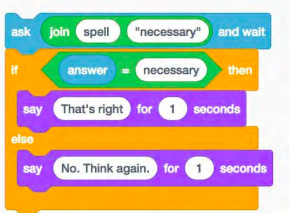

It’s also highly remixable - we can take this outline of code and make it a 20 question test, or keep track of the score, or work on the user interface so it’s just a bit more funky than text on screen, or any number of other possibilities. For example, as well as testing tables, could we use code like this to test spellings? Well, maybe. Asking the question is easy enough:

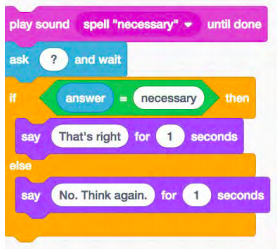

But alas this is now just a little too easy as a spelling test. We could record some audio and play that, but then it’s not a very flexible bit of code:

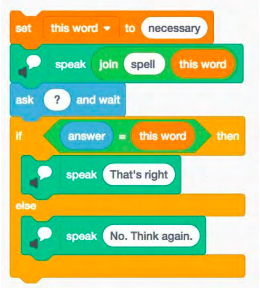

But now in Scratch 3, we’ve access to text-to-speech blocks as one of the standard extensions (libraries). Click on the button at the bottom left of the window and then select the text to speech extension.

So what about applying this idea to learning other languages? Well, clearly we can just check answers to questions, for example:

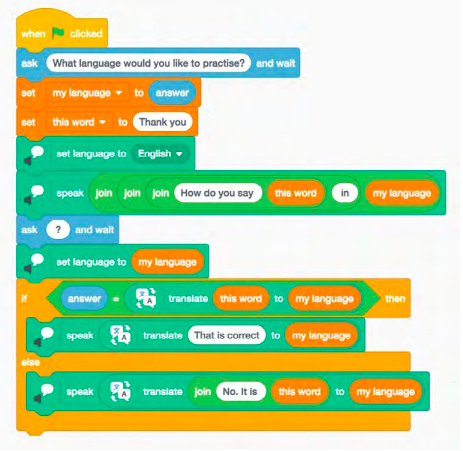

We can go further than this though, using the Google Translate extension / library to look up the word in our target language, and then the program can be used to test any language, or at least any of those that Google Translate knows about.

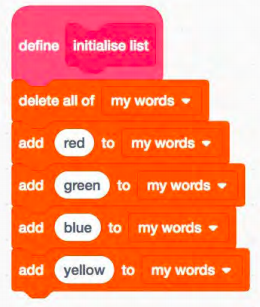

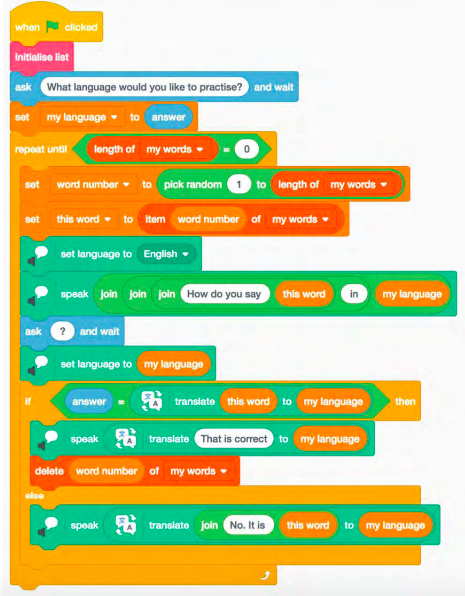

It’s worth pointing out a couple of other refinements in the code here. Notice that we’re giving the feedback in the target language rather than in English, and if the user gets the translation wrong then we helpfully tell them the correct translation, in the chosen target language. We also change between English and the target language for the text to speech blocks, so that the pronunciation for the question and for the feedback is correct - it’s quite fun to experiment with the different language settings here, for example using French to pronounce English… The last stage is to do something about the range of vocabulary we’re testing - the version above just tests “Thank you”, which is certainly important vocab, but typically you need a few more words to get by. Let’s introduce the idea of a list as a way to keep track of all the words we need to practise, initialising this when we start the program with a custom block (or you could use a broadcast message instead):

We can then simply pick our target word from the list. Note that our code here removes words from our vocab list when we get them right, but leaves them there for another go if we get them wrong.

Taking it further

-

There are plenty of ways to improve the user interface here. What might you do?

-

Can you keep track of the player’s score, or impose a time limit? How does Google translate work?

-

Is there any way to allow for more ‘fuzzy’ translations? Should ‘danke’ and ‘vielen dank’ both be awarded the points for translating ‘thank you’ into German?

-

The Scratch team have been working on voice to text - how could you incorporate that in your code?

Originally published in Hello World 7

Share