Patterns in Scratch

Mar 16, 2021

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, Logo’s ‘turtle’ graphics was many children’s introduction to computer programming in school (Papert, 1980). By creating scripts using simple commands like move forward, turn left, turn right, pen up and pen down for an on screen ‘turtle’, simple geometric figures and complex patterns can be drawn on screen. Turtle graphics is often introduced in the maths curriculum, where it can be used for investigating the properties of quadrilaterals or regular polygons, but once a degree of fluency has been achieved with the commands of the language,it provides rich opportunities for creativity under constraints.

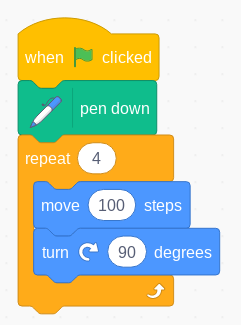

Pupils might start by creating a program to draw a square on screen:

Figure 1 - Scratch program to draw a square

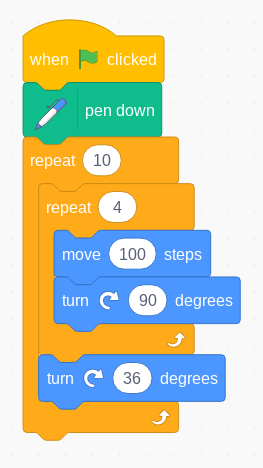

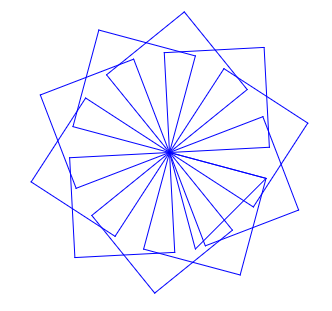

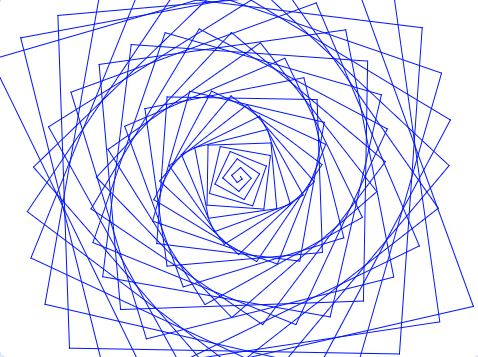

By repeating the repeat 4 loop here (‘nested repetition’), a rather pleasing ‘crystal flower’ figure can be drawn:

Figure 2 - Scratch program for a figure made of ten squares

Figure 3 - image created by running the above program

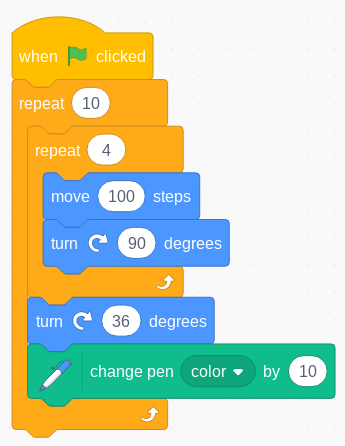

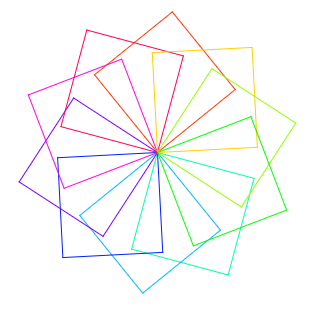

The Scratch pen library also allows the colour of the line drawn to be controlled, thus

Figure 4 - Scratch program to produce ten colour squares

Figure 5 - Ten coloured squares

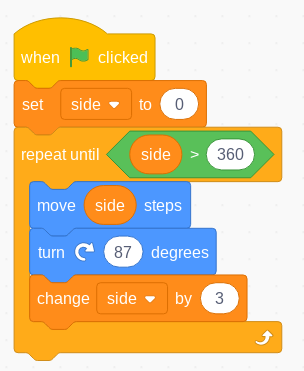

More complex figures can be drawn by introducing variables, so that the length of the sides drawn change at each step:

Figure 6 - Scratch program for a roughly square based spiral figure

Figure 7 - Result from the above program

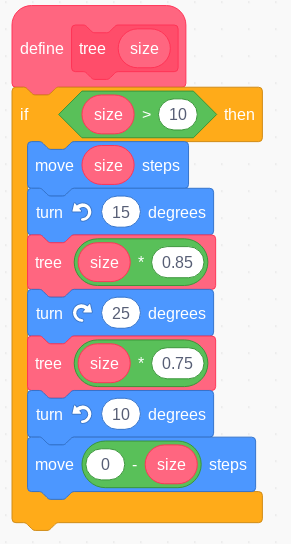

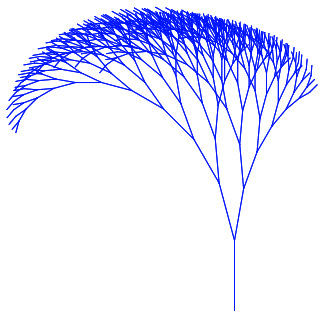

Once pupils are comfortable working with Scratch and understand what programs such as those above can do, allow them simply to play or experiment with these commands to see what patterns they can make Scratch draw. They should be encouraged to think about which patterns are particularly pleasing to the eye, and what makes them so. Although normally beyond the scope of primary computing, turtle graphics can be used to explore self-repeating fractal figures, perhaps taking inspiration from ferns, trees or broccoli. Here the programmer creates their own custom block which refers back to itself.

Figure 8 - custom block to create a fractal ‘tree’ in Scratch

Figure 9 - the resulting image

This approach to exploratory, playful programming might seem rather removed from the top-down, problem solving approach suggested by the elements of computational thinking, but it is through this more grounded, learner centred approach that a primary-aged pupil forms their own understanding of ideas such as abstraction, decomposition, patterns and algorithms. Just as Piaget might have argued that a child comes to understand conservation of shape and number through playing with physical building blocks, so a child might come to learn how a computer program works by playing with the code building blocks from which it is made.

Reference

Papert, S., 1980. Mindstorms: children, computers, and powerful ideas. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Share