Programming

Mar 14, 2021

Programming is the process of taking an algorithm (a sequence of steps or set of rules that solves a given problem) and translating that into the instructions, the ‘code’, that the computer can follow. There are many programming languages available, but all have in common the property that they can be understood by both humans and computers. Because they can be understood by people, programming languages use human language (typically English), either in a graphical form such as the building blocks of Scratch, or as typed text, in traditional languages such as Logo or Python. Because the language has to be understood by a computer, they are only ever a defined subset of a human language, much less flexible, and have a precise, formal specification, leaving no doubt about how instructions in the language are to be interpreted by the computer. The Key Stage 2 programme of study for computing makes reference to six particular programming constructs: sequence, repetition, selection, variables, input and output. These six building blocks are all that’s needed for programming the solution to any problem that can be solved by a computer (Böhm and Jacopini, 1966).

Sequence

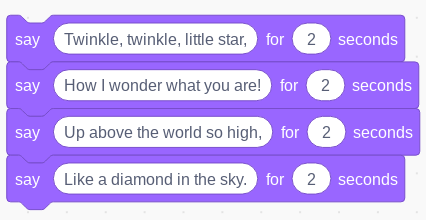

Computer programs are typically made of sequences of instructions, followed one after the other. At a young age, pupils might learn to program simple robots such as the Bee Bot, where a particular sequence of key-presses are followed by the toy. Later on, pupils might create a sequence of movement, speech or music instructions for a Scratch sprite to play back, such as this:

Figure 1 - Scratch program for a nursery rhyme

Repetition

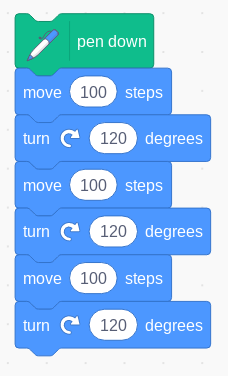

When pupils begin to see the repeating sequences of instructions in their algorithms, they can use repetition (also called ‘iteration’) in their programs to make the computer follow these, without the need to write the same instructions multiple times. Repetition can involve instructions being repeated forever (or at least until the program is stopped or the computer turned off), a fixed number of times or until some particular condition is satisfied. For example, the Scratch code here is a sequence of instructions to draw an equilateral triangle:

Figure 2 drawing an equilateral triangle as a sequence of instructions

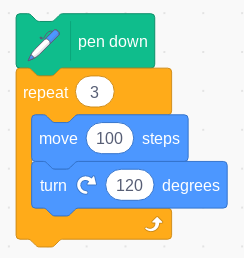

Notice that the same move 100 steps, turn 120 degrees instructions are repeated three times, so using repetition would give the simpler program below:

Figure 3 - drawing an equilateral triangle using repetition

Selection

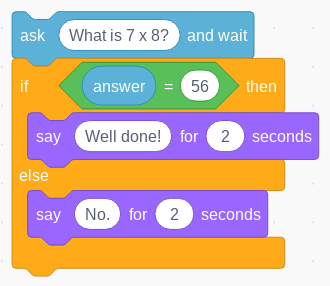

The power of computer programming does not rest on creating or repeating sequences of instructions, but rather on the ability for the computer to execute different sequences of instructions depending on whether some internal or external condition is met. To do this, the programmer makes use of selection, typically in the form of if … then … else statements. For example, the following Scratch program would tell the user whether they have correctly answered the question it asks:

Figure 4 - Checking if an answer is correct using selection

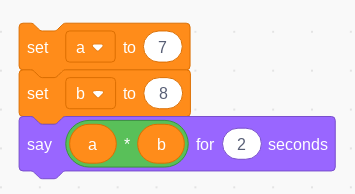

Variables

Computer programs are also able to keep track of how information changes as the program executes or accepts input from its user. There are many ways to organise the information appropriately for the particular problem, but primary pupils are unlikely to need anything more complex than variables: single, named locations in the computer’s memory. These locations might store true or false values, numbers or strings of characters such as words or sentences. In Figure 4 above, ‘answer’ is a variable, storing whatever information the user typed in response to the question. In the example below, we store two numbers in variables a and b and display their product (using * to perform the multiplication):

Figure 5 - performing a multiplication using two variables

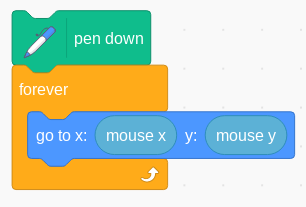

Input

We also need some way of getting information into a running computer program: this is called input. Figure 4 above is an example of input, using the keyboard to type in numbers or text. Scratch programs might also use mouse or trackpad movement, the microphone or the webcam for input, or respond to particular events such as mouse or trackpad clicks or particular keypresses. With a suitable interface, other input sensors such as switches, light sensors or temperature probes could also be used. It is worth noting that any input has to be converted into a digital (that is, numerical) form before it can be processed or stored, although the user or programmer rarely has to worry about the details of this conversion.

As an example, the following program turns the trackpad or mouse into a simple drawing tool:

Figure 6 - turning the mouse or trackpad into a drawing tool

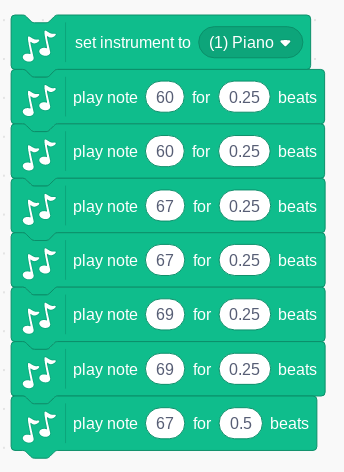

Output

Computer programs also need some mechanism for getting information back out to their user, called ‘output’. The example programs above have included displaying text on the screen, as dialogue ‘spoken’ by the Scratch character, as well as drawings on the screen. As well as displaying information visually, either as text or graphics, programs can produce audio output through the speaker or headphones (such as music, playing back recorded audio, or synthesised speech). With a suitable interface, a program might control lights or motors including those of a robot. The example below plays the first few notes of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star (in the key of C):

Figure 7 - playing back a sequence of notes

Once pupils have grasped the idea of these six programming constructs, they are in a position to make use of the computational thinking problem solving strategies to apply these in a wide variety of projects. These might begin with some highly scaffolded examples led by the teacher, but as pupils become increasingly fluent with the problem solving techniques of computational thinking, and the expression of these programming constructs in a particular programming language, such projects should encompass independent, open-ended creative projects.

Reflection

Which of these concepts is easiest to understand? Which would be easiest to teach? Can children learn these through studying example programs or responding to challenges, or should they be learnt through integrating these into creative projects? Can you think of examples from elsewhere in the curriculum where pupils might put these into practice?

Reference

Böhm, C. & Jacopini, G. 1966, ‘Flow diagrams, turing machines and languages with only two formation rules’, Communications of the ACM, 9, 5, 366–371.

Share