Storytelling in Scratch

Mar 18, 2021

There are many ways in which pupils might use digital media to tell a story: they could simply type their story into a word processor, or record themselves telling (or reading) their story; they could create a presentation based on their story, perhaps adding a recorded narration to this; they could create a stop-motion animation, taking a series of photos of a 2- or 3- dimensional scene and characters as these are slowly moved, then playing these images back to create the illusion of movement; or they might act out their story with some classmates, recording their performance as digital video.

Scratch provides a further possibility: pupils can program a scripted animation of their story. Pupils can create their own (or use the provided library of) sprites and backgrounds suitable for their story. They would then think carefully about the algorithm (the sequence of steps) for the story they want to animate, perhaps focussing attention initially on dialogue and action. They need to ensure that actions and dialogue are synchronised between the different characters - pupils might initially do this by working on a timeline, for example:

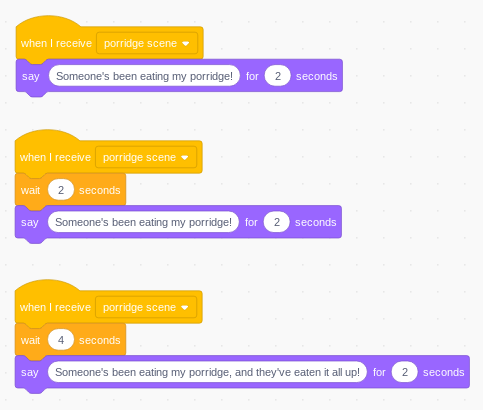

Figure 1 - synchronising dialogue through timing

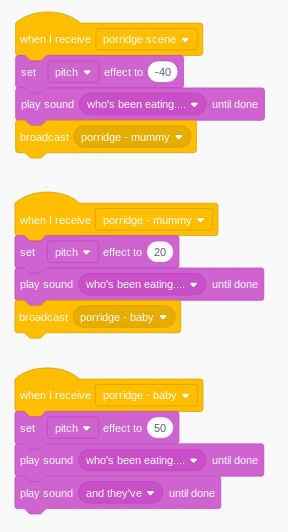

Note here the scripts would be executed by each of the three bears, and that these are all started by the broadcast message. The timings ensure that only one piece of dialogue is displayed at a time. Another approach might be to record the audio to be played by each bear - this is a more engaging approach to animation, as effective practice in multimedia is to use both audio and video together. With careful timing, recorded audio can be synchronised, but it is easier to use Scratch’s message passing to synchronise the behaviour of each of the three sprites:

Figure 2 - synchronisation using broadcast messages

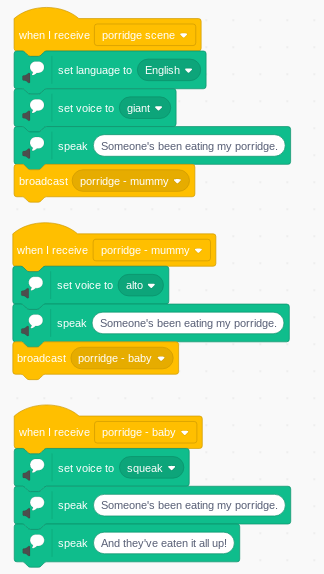

This approach can be harder to keep track of than detailed timing based synchronisation, but it does make it easier to adapt what happens as a program is developed iteratively, and is closer to replicating how a conversation actually takes place, with one character responding to another rather than speaking at a predetermined time. Pupils might also experiment with Scratch’s text to speech extension, to have the computer speak the dialogue itself rather than playing back their recordings:

Figure 3 - using text to speech in Scratch

Incidentally, this can be an interesting way to have pupils think again about grapheme / phoneme correspondence, considering how Scratch can be ‘taught’ to read text aloud. It can be amusing to change the language setting here as this changes the grapheme-phoneme correspondence from that of (American) English to that of the other language, producing heavily accented English speech.

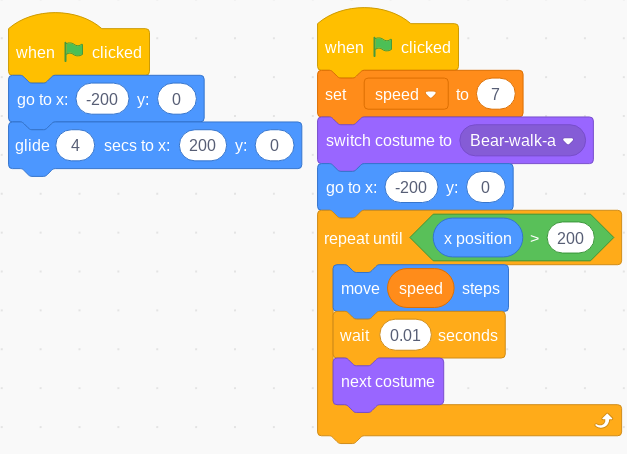

It is easy enough to program characters in Scratch to appear or hide and to move to predetermined positions on screen. Initially this may be enough for pupils’ animated storytelling projects. More effective animation would involve small changes to the appearance of the character’s costume, to create the illusion of, for example, walking, or of the character’s mouth moving as it eats or speaks. Thus, to animate a bear walking across the screen pupils might replace the left hand script with the right:

Figure 4 - two approaches to animating a bear moving across the screen

The different costumes can be created using Scratch’s vector graphics editor by making small changes from one costume to the next. Scripted animation provide an excellent opportunity for developing computational thinking: abstraction is used as pupils pay attention to just enough of the detail to tell the story and draw characters and scenes; decomposition takes place as pupils break a complex project and story down into components; pattern recognition is learnt as they see how broadcast messages and costume changes can be used in many different ways; and pupils translate their stories into a clear sequence of steps as an algorithm before expressing that in the language of Scratch code. Animation projects are particularly suited to pair or small group work, recognising that producing digital media is almost always a collaborative process.

Share