Op Art with p5.js

Mar 15, 2023

The national curriculum requirements for Key Stage 3 computing include that pupils are taught two programming languages, at least one of which must be ‘text-based’. Most schools satisfy this through continuing with Scratch into Year 7, and then introduce Python. I’m a huge fan of Python - I love the way it can be used in object-oriented and functional paradigms, the elegance of its syntax, and the huge variety of libraries available. It’s used in some motivating, real world contexts such as machine learning and data science. For someone who wants to get useful things done with programming in other contexts, rather than just pursue a career in software development, Python is a great choice.

That said, it’s hard to see this as particularly motivating for most pupils. For those who’ve grown up making animations, interactive stories and games in Scratch, it’s hard to see the motivation for the extra, intrinsic cognitive load of Python that comes through creating a text-based drill and practice maths game! Processing, particularly in its modern, web-based p5.js incarnation, provides another approach for the transition to text-based programming, which my limited anecdotal evidence suggests is far more motivating for most teens. Processing ditches a text-based focus for programming, favouring instead the idea of creating a visual ‘sketch’ that can be run and modified in real time. We worry less about the internal state of variables, arrays and flow control, as we can see immediately the effect of running and changing code, just as we can in Scratch.

As with Scratch, p5.js lends itself to creative coding, but I’d recommend introducing it in a more scaffolded, problem-solving way, recognising that novices and experts learn differently, and that, with any new language, all my learners are likely to be novices. One approach to ‘problem solving’ in the arts is to take inspiration from existing art, and to try to recreate it. Bridget Riley’s work seems ideal for this.

Riley (1931-) is a British artist, best known for her ‘op art’ - paintings that deliberately play tricks on the eye, and share some characteristics with optical illusions. I first encountered her work as a student, and was immediately captured by the geometry and colour. I’ve been a fan ever since, and fondly recall taking a group of pupils up to Tate Britain to see a retrospective of her work in 2003: on our return to school we used Inkscape (open source vector graphics software) to create our own versions of her work - there are some lesson based on this in Year 4 of my Switched On Computing. My father in law printed a number of her catalogues, and tells the story of having to phone her to ask which way round a particular plate should be printed. She replied that she’d need to check where she’d signed the original.

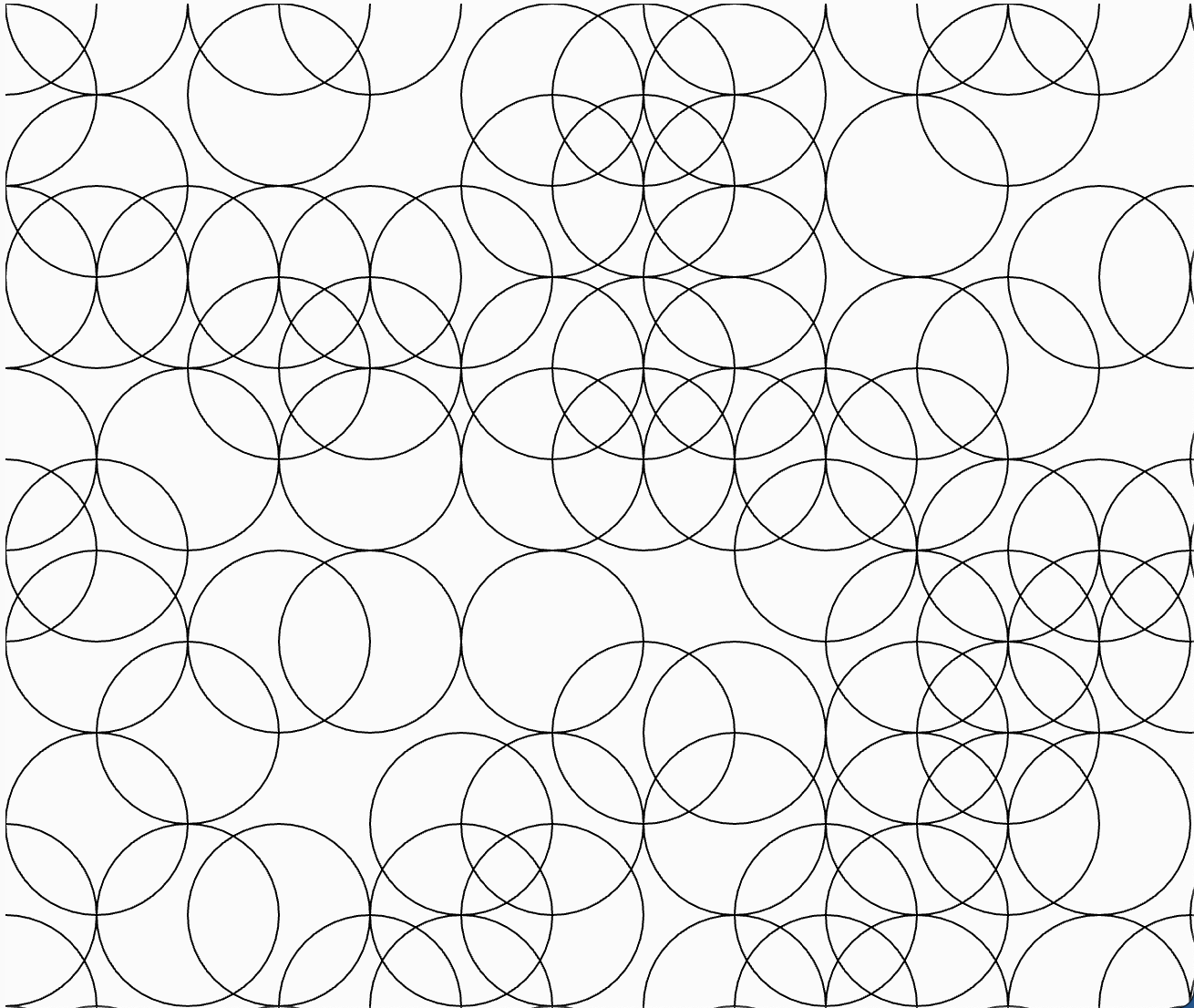

Composition with Circles

When teaching programming in p5.js using Riley’s work, I’ll typically start with Composition with Circles (2003), remembering seeing this as a mural on that school trip. We’ll start, perhaps, with a single disc in the middle of the canvas, before using repetition to make a whole line of circles:

diam = 100;

function setup() {

createCanvas(windowWidth, windowHeight);

noFill();

for (x = 0; x < width + diam; x += diam / 2) {

ellipse(x, height / 2, diam, diam);

}

}

I code this in p5.js’s setup() procedure, which runs once - this is fine for creating a static image such as this. I comment out the background refresh in p5.js’s draw() procedure, which runs every time the screen refreshes - there’ll be time to experiment with animation and interactivity late. The noFill() here draws just the circle’s edge, rather than a filled disc. Filling the canvas with overlapping circles involves nesting this x loop inside a y loop, creating a grid that reminds me of non-representational Islamic art. To come closer to Riley’s original, I’ll add a selection statement inside the x loop, only drawing circles maybe 50% of the time:

diam = 100;

function setup() {

createCanvas(windowWidth, windowHeight);

noFill();

for (y = 0; y < height + diam; y += diam / 2) {

for (x = 0; x < width + diam; x += diam / 2) {

if (random() > 0.5) {

ellipse(x, y, diam, diam);

}

}

}

}

Once we’ve got to this point, I’m reasonably happy that we’ve achieved a close match to Riley’s original work, but we might go on to explore some ways of making this an animation or making it interactive by moving the circle drawing inside the draw() procedure, or simply adding it to p5.js’s mousePressed() procedure, so that we can generate a new set of circles by clicking the mouse.

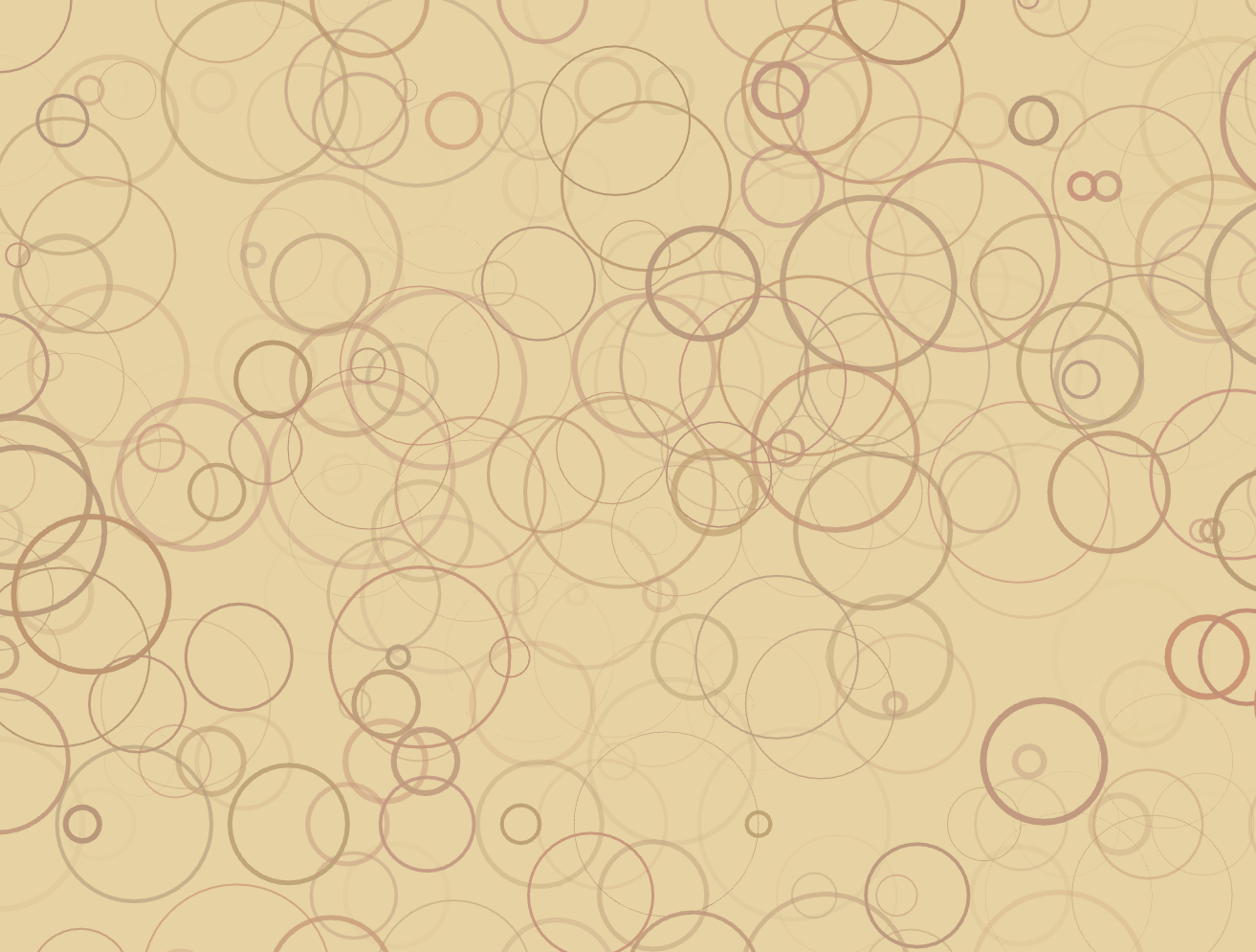

Options here might include changing the likelihood of drawing a circle, varying the size of the circles, including using random sizes, filling in the circles with semi-transparent colours from the full or a restricted palette, or pretty much anything really! Here’s a version that reminds me of coffee stains, which moves us some way from Riley’s own work. Is this still problem solving, or is it now creativity? Does tweaking a few parameters really count as creative work?

function mousePressed() {

diam = 1;

background(230, 210, 160);

for (y = 0; y < height + diam; y += diam / 2) {

for (x = 0; x < width + diam; x += diam / 2) {

if (random() < 0.6) {

stroke(

random(180, 200),

random(140, 160),

random(110, 130),

random(255)

);

strokeWeight(random(7));

diam = random(20, 200);

ellipse(x, y, diam, diam);

}

}

}

}

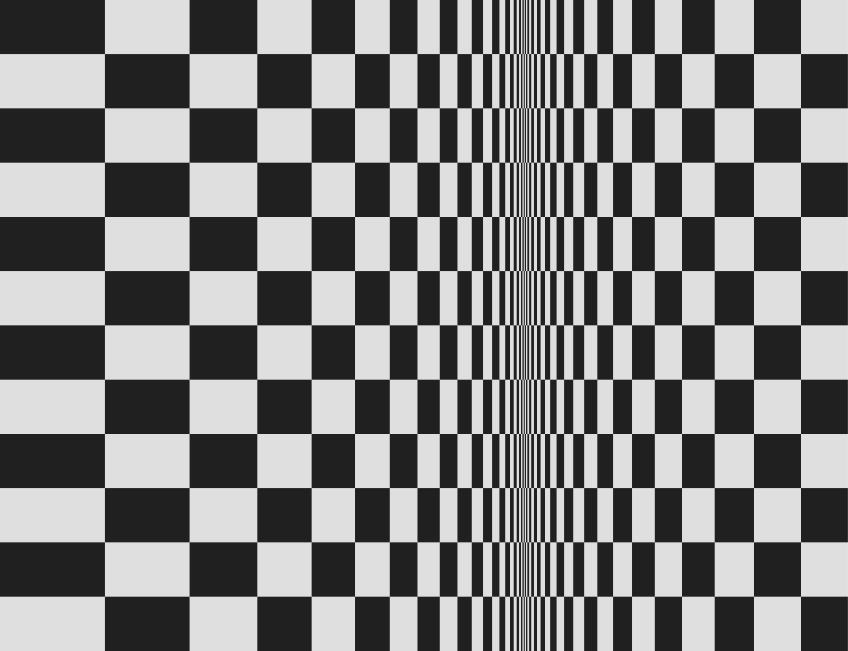

Movement in Squares

I’ve several more examples of sketches (Processing’s name for programs) inspired by Riley, e.g. Achæan (1981), Nataraja (1993), Cataract (1967), for which the maths is a bit harder, and Nineteen Greys (1968), which makes use of translations and rotations. Here, though, let me walk you through one more, Riley’s iconic, monochrome Movement in Squares (1961).

We start here with creating a chequer board of 12 rows of alternating black and white squares, again working initially in the setup() procedure:

function setup() {

createCanvas(windowWidth, windowHeight);

w = width / 12;

h = height / 12;

c0 = 255;

for (y = 0; y < height; y += h) {

c0 = 255 - c0;

c = c0;

for (x = 0; x < width; x += w) {

c = 255 - c;

fill(c);

rect(x, y, w, h);

}

}

}

Riley’s Movement in Squares isn’t a regular chequer board though - the width of the squares varies across the canvas. We can achieve this by changing the w increment inside the loop for each row.

w = 0.2 * abs(x - 0.618 * width) + 1;

The above formula works well enough, but note the + 1 (or something larger than 1) is crucial here - JavaScript is much less forgiving than Python if it finds itself in an infinite loop, and the p5.js coder quickly gets used to saving their work frequently!

As before, this gets us very close to Riley’s original, and provides a jumping off point for our own more creative work, for example varying the height and width of our squares according to the mouse position, as here, again inside the draw() procedure, which runs every time the screen refreshes.

function draw() {

background(255);

c0 = 255;

for (y = 0; y < height; y += h) {

h = 0.2 * abs(y - mouseY) + 1;

c0 = 255 - c0;

c = c0;

for (x = 0; x < width; x += w) {

c = 255 - c;

fill(c);

w = 0.2 * abs(x - mouseX) + 1;

rect(x, y, w, h);

}

}

}

Life, pandemics and turtles

There are lots of other things that pupils could do with p5.js. I’ve worked with students to create Conway’s Game of Life and to model the spread of a epidemic. This is a really nice way to introduce object oriented programming, as I’ll start by creating a class of balls bouncing around the canvas with location and velocity properties and move and show methods, and then extend this to a class of patients, adding in status as a property, adding get and set methods for this and overriding the show method.

Unlike Scratch and Python, p5.js offers no built-in turtle graphics library, but it does offer the tools to build one - implementing turtles as a class, with properties such as position and heading and methods like move and turn. The coding here requires a little knowledge of trigonometry, but it’s accessible to GCSE students.

CS NYC have a very nice introduction to computational media high school curriculum which uses p5.js, which builds to a capstone project of creating album art. There are some excellent self-study resources available, and none are better than Daniel Shiffman’s The Coding Train YouTube channel. I gave a talk on creating Op Art inspired by Bridget Riley at CSTA’s virtual conference back in 2021; the recording is online here.

Share