Games in Scratch

Mar 19, 2021

The examples in the three previous posts (patterns, composition and storytelling) use sequence, repetition and output, with some limited use of variables, but if pupils are to learn about selection, input and more extensive use of variables, their Scratch programming must extend the range of media they develop to include interactive elements, for example by making a video game.

Pupils’ stories can often be adapted into games, for example modifying a traditional, linear narrative into a branching, choose your own adventure game by including input blocks and then if … then … else blocks to determine how the story continues according to the input the player provides. From a computational thinking perspective, this introduces pupils to a tree-like pattern which has wide ranging applications in subsequent programming.

Pupils’ own media use is likely to encompass a wide range of computer games as well as more passive forms of media, and these games might provide some inspiration for their own creative work in Scratch. Initially, pupils might be better served by developing their fluency in Scratch programming through working with relatively simple games rather than face the frustration of not knowing how to implement a sophisticated idea from a familiar, modern game. The classic games from the 1970s and 80s are worth revisiting as a starting point.

Mazes

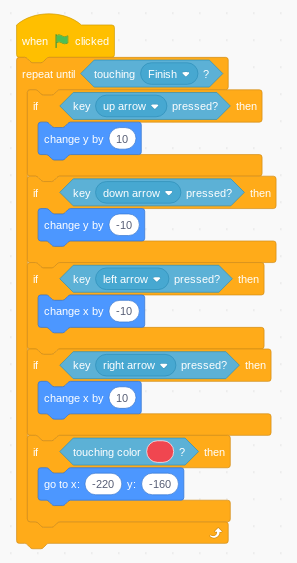

In a maze game, such as the classic Pac Man, pupils would create a background of a maze to find a path through, with a predefined starting point and exit. Controlling the player’s character could be done using the cursor keys, moving the character up, down, left or right by changing the sprite’s y or x coordinate according to the key pressed. Pupils could program the sprite so it can’t cross the walls of the maze, or increase the sense of jeopardy in the game by making the character return to the starting point each time it hits the walls. The basics of the program might be as follows:

Figure 1 - Scratch script for a character in a maze game, returning to a starting point at the bottom left if it touches the red walls of the maze

Once pupils have created a basic maze game using code like this, they can then let their creativity run free by making the game their own - can they introduce additional hazards into their maze? Could they modify the game so that it has progressively more difficult levels? Could they introduce a time limit, or a limited number of lives? Could they have the character be chased around the maze by a computer-controlled character? Could there be items to collect as they find their way around the maze? Can they introduce some sound effects, background music or create animated costumes that change as their character moves around? This ‘iterative development’ approach is common in software engineering, where a ‘minimum viable product’ might be used to prove the concept or test the market before more features are gradually added in response to requests, testing or feedback.

Catching

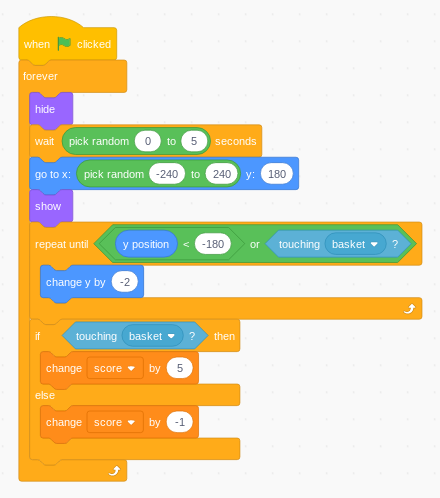

Imagine a game in which a player moves a basket from left to right collecting, say, apples as they fall down the screen, or avoiding falling rocks. It’s easy enough for pupils to make something like this in Scratch. The control for the basket is very similar to the control program for the character in the maze game above, but this time we only need to allow movement along the x axis. For each of the falling apples we might have a script like this:

Figure 2 - script for a falling apple

Notice here the use of random numbers, used for both the delay before an apple appears and starts to fall and for the position at the top of the screen from which it falls. Notice also how this script makes use of two different types of repetitions as well as selection and variables.

As with the maze game example, pupils’ creativity here is expressed through modifying a minimal example: perhaps adding in other objects to catch (e.g. other fruit) or avoid (e.g. stones); making objects progressively speed up through using a speed variable; perhaps even modelling acceleration under gravity; adding a time limit or even aiming objects at or away from the player’s basket.

Pong

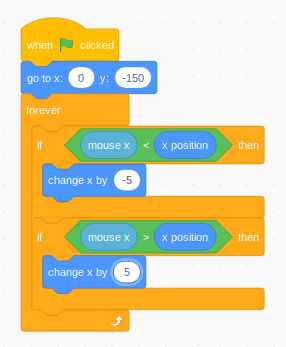

Pupils might also create their own version of the classic ‘tennis’ game Pong, perhaps starting with a one player version. Here the paddle can be controlled using the keyboard, with similar code to the maze game or catching game, or it could move to a position determined by the mouse:

Figure 3 - mouse / trackpad control for a paddle

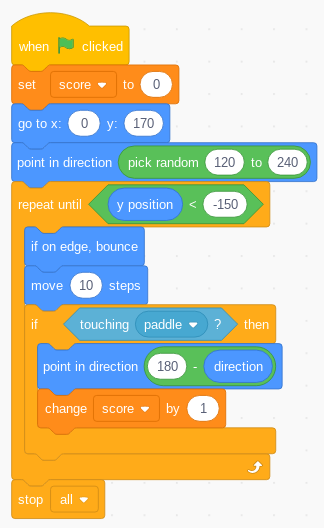

The script for the ball needs to control how the ball bounces when it hits the paddle. Teachers could simply give pupils model code such as the following here, but it may be more instructive for pupils to experiment with different instructions, to see which might be more realistic or which might make more interesting games.

Figure 4 - script to control a ball in a Pong game

Pupils may find it interesting to see how different paddle and ball shapes behave in this game. From a starting point like this, pupils could then experiment with creating a Breakout style game in which the ball gradually demolishes a wall of bricks in the upper part of the screen, or create a two-player version of the game, with each player using the keyboard to control their own paddle.

With suitable scaffolding, using the problem solving structure provided by computational thinking and the programming constructs discussed above, pupils could engage in independent or collaborative projects to develop their own, original computer games in Scratch: genres such as platform games, driving simulations and puzzles all offer rich opportunities for creative work.

Reflection

Which of these ideas appeals to you most? Do you think all pupils would find these equally engaging? Do you think there may be gender or cultural differences in how engaging pupils find these activities? How much scaffolding is appropriate for creative work in computing? How would you ensure appropriately adaptive teaching or differentiation in using project ideas like these?

Share